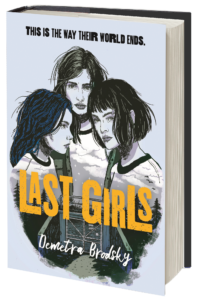

Demetra Brodsky’s Last Girls is a twisting, suspenseful YA thriller about sisterhood, survival, and family secrets set in the world of doomsday prepping.

No one knows how the world will end.

On a secret compound in the Washington wilderness, Honey Juniper and her sisters are training to hunt, homestead, and protect their own.

Prepare for every situation.

But when danger strikes from within, putting her sisters at risk, training becomes real life, and only one thing is certain:

Nowhere is safe.

Read an excerpt of Last Girls coming May 5th.

[dropcap type=”circle”]T[/dropcap]he end is drawing near. Either my sister Birdie pulls her act together and finds her Every Day Carry, or we’re leaving without it. She can deal with the consequences if today is the day the shit hits the fan. I shouldn’t joke. You never know. But it’s stupid, really, since Birdie is usually the one who’s most prepared, at least physically. The prize for most prepared emotionally goes to our youngest sister, Blue. She’s the one least likely to get flustered. A calm blue sea with hair to match, which is why it’s unusual to see her in a flurry, tossing saggy, beige couch cushions aside and sliding heavy wooden furniture around to help Birdie search. Not me. I’m waiting with my arms crossed. If Birdie wants to fly out at night to meet Daniel Dobbs from The Burrow, she should have prepped her EDC before squeezing her bedraggled butt through the window and down the cucumber trellis last night.

[dropcap type=”circle”]T[/dropcap]he end is drawing near. Either my sister Birdie pulls her act together and finds her Every Day Carry, or we’re leaving without it. She can deal with the consequences if today is the day the shit hits the fan. I shouldn’t joke. You never know. But it’s stupid, really, since Birdie is usually the one who’s most prepared, at least physically. The prize for most prepared emotionally goes to our youngest sister, Blue. She’s the one least likely to get flustered. A calm blue sea with hair to match, which is why it’s unusual to see her in a flurry, tossing saggy, beige couch cushions aside and sliding heavy wooden furniture around to help Birdie search. Not me. I’m waiting with my arms crossed. If Birdie wants to fly out at night to meet Daniel Dobbs from The Burrow, she should have prepped her EDC before squeezing her bedraggled butt through the window and down the cucumber trellis last night.

It’s funny how Blue is the most unflappable. When you think about it, logically, that trait should belong to Birdie based on her name. Are names logical? I don’t know. Maybe Blue’s, but not mine. Women spend their whole lives cringing whenever someone calls them honey. Not me. No sirree. Mother named me Honey at the outset, so I don’t get to be offended. As the oldest, I don’t get to be anything except Responsible, Reactive, and Ready. The three big Rs. Even if that only means having a good comeback ready when necessary, which is more often than you’d think.

“Today will be the day she needs it,” Blue says. She’s prone to matter-of-fact statements. There isn’t an aggressive bone in her body. She’s just self-assured and has clear . . . opinions. Sure. Let’s call them that.

I flick my eyes to them and sigh. “We have to go, Birdie. Blue and I have our bags. Just stick to the evacuation plan if needed. We got you.”

Birdie blows a curtain of thick bangs away from eyes dark as a storm, deepened more at the moment by her annoyance with me. “Seriously, Honey? You’re not even gonna attempt to help me attempt to locate my EDC? You heard Blue.”

I heard her. And it’s not that Blue’s proclamations don’t often come true. They do. Out of all us weirds, she’s at the top. It’s just the world as we know it hasn’t ended in the ten years we’ve been preppers. Not when it was just us stockpiling food and water. And not in the year we’ve lived in The Nest.

I roll my own, less contemptuous brown eyes at Birdie and walk out. Blue is right in a way, and so is Birdie. Preparedness is the root of prepping. But I’ll bet my favorite Gerber folding knife, dollars to doughnuts, my sister left her EDC outside last night. Love makes you do stupid things. Not that I’d know. God forbid I have time for a boyfriend. Even if I did, none of the Burrow Boys appeals to me, and Outsiders are offlimits. For me, it’s a zero-sum game.

I hear Birdie grumble, “Typical,” as I walk to the kitchen and it puts a hitch in my step. As long as they’re following me, it doesn’t matter. I wait one second, two . . . expecting them to walk through the doorway and grab their lunches from the table.

Guess not.

Mother glances up from the self-inflicted palm wound she’s treating with homemade antibiotics, concocted in our kitchen from bread mold left to grow in the large bay window. The plants filling the same space provide necessary humidity for the process, turning that windowsill into Mother’s makeshift laboratory. Complete with microscope and glass beakers. A mix of aluminum and copper pots hang above her head from an oval rack, and bundles of drying herbs are hanging from the wooden rafters. Some of the pots in this kitchen are used for cooking, others for her medicinal experiments. We’ve had to learn which is which.

Typical.

Sure, Birdie. That’s us Junipers in a nutshell.

“You could be more patient.” Mother’s expression is serious, despite the youthful brown freckles covering her face, including her thinning lips. “You remember when you were a junior, all the things you had to worry about: SATs, driving, piled on top of threats of global warming, economic collapse, a possible viral flu pandemic. You never know how long you girls will have with each other. None of us do. You could be the last girls on this compound. All we can do is prepare, not predict.”

Prom and nuclear war, final exams and EMPs, college ideations and bug-outs: Mother loves to throw prepper worries into the mix of things that are typical to most high schoolers. Most, but not all. There are other kids like us in The Nest and The Burrow. Girls to the left. Boys to the right. That setup is another story.

“I was hoping we’d get to school early enough for me to work on my self . . . by myself, on a lab assignment for chemistry,” I correct my mistake mid-telling. “No worries, though. I have an idea where Birdie’s EDC might be.”

I turn to head outside and she calls me back. Her voice a butter knife scraping burnt toast until she clears her throat.

“I wasn’t aware you had an added interest in chemistry.”

Mother takes a glass dropper and lets three fat blobs of a yellow tincture fall onto a petri dish.

I didn’t say that. Not exactly. Mother hears what she wants. Through a filter of her own interests, which are not always the same as mine.

“The chemical reactions are cool,” I offer, watching her work at the heavy kitchen farm table.

Chemistry is great. Don’t get me wrong. I’m good at it. One of the best in my class, but I wouldn’t call my interest added. It was just the first thing that popped into my head when I stopped myself from saying I was working on a self-portrait. Prepping comes first. Always. The rest—art, literature, music—is extra. Frivolity. According to Mother. The work of dilettantes. On that viewpoint, we’ll have to agree to disagree. I’ll prep. I’ll plan. Hell, I’ll show every Nest Girl and Burrow Boy on this compound I can be ready in a flash, just as quick as any one of them if not quicker, on any given day. But if the world does end tomorrow and we have to rebuild society, wouldn’t we want the arts to be part of that again? I would. I think there’s room for both.

That’s my real added interest. Society without culture might as well be dead. An extreme position, I know. What can I say? I’m a doomsday-prepping enigma.

Thankfully, I’m not alone.

A knock on the screen door’s wooden frame grabs our attention. Mother stands and waves Ansel Ackerman inside.

Most of the guys in The Burrow wear some version of the same uniform, so to speak. Cargos, crewnecks, button-down flannels. Ansel is wearing a monochromatic version today. A human licorice stick in black cargos, black bomber jacket, black boots. I don’t mean that in a tasty way.

“Hey, Honey. Guess I’m not the only one running late today.”

“We should blame traffic,” I tell him.

Ansel blinks his extra-long lashes before realizing that’s a joke. There’s no traffic on these rural roads. Being late would be entirely our fault. Birdie’s fault, in my case.

“I have everything ready for you,” Mother says, handing Ansel jars of homemade tinctures and the sack of veggies she pulled from the garden.

“Thanks,” he says, but won’t look at her.

The leader of the compound’s son has been sheepish around her lately. I understand why, but haven’t had the nerve to say anything to her or him yet. I hold the screen door open for him and he says, “See you among the sheeple.”

“Different day, same herd. Baa!”

He grins again, only that’s not a joke. Most Outsiders do live like herded sheep. Grossly unprepared for any number of impending threats that could cause The End Of The World As We Know It.

We’re preparing for TEOTWAWKI by homesteading. Ansel comes to our house every third Wednesday to pick up medicine, eggs, vegetables, or goat’s milk, alternating pickups from the other all-female households that make up The Nest. The Burrow, where he lives, is in charge of all things tactical. Artillery, weapons, ammunition, explosives. Things to ensure operational security in the event of an EMP that wipes out all power or a nuclear attack. We all train together in weapons usage, hand-to-hand combat, and survival skills under the radar of our casual acquaintances. On a day-to-day basis, I think The Nest is the more important garrison. We all have to eat and take medicine whether the world is ending or not.

I head outside while Mother’s back is turned and walk around the side of our cedar-shingled house before she regroups and prods me again about my chemistry project at school.

Birdie’s Every Day Carry is exactly where I suspected. Perched on the low-shingled roof outside our bedroom, where we sit to stargaze whenever we need a few minutes to chill and pretend we’re just like everyone else. Well, I do most of that kind of daydreaming with Blue, really. Birdie embraces being different, most of the time. But in those off instances when she doesn’t, when she’s tired and had enough, I have to watch her or she’ll get into it with Mother, and we’ll all pay for Birdie mouthing off. Prevention is the best safeguard for conflict. I guess that’s a form of prepping, too.

I whistle long and low with a sharp uptick at the end, so my sisters know to come find me. The flash of Blue’s cobalt hair enters my peripheral vision as they round the corner and I point at the roof.

“Oh.” That’s all Birdie says. Her version of sorry I acted like a crazy person.

Blue laughs in her husky-voiced way. She’s sounded like an old woman that smokes three packs a day since she could first speak. The voice of someone who’s seen more than her years.

“You snuck out again and left that, of all things, there?” “Shhhh.” The hush comes from Birdie and me simultaneously.

“Do you want to spend a night in the bunker?” I ask.

Blue shakes her head. She hates being down there the most.

“Well,” I tell Birdie. “Go get it. Hurry up.”

Fly, Birdie.

She ties her buffalo-plaid shirt around her waist and climbs the same trellis she used to get herself into this predicament. The red-and-black cuffs on her shirt are fraying, the seat of her black jeans wearing thin. Not that Birdie cares. She’ll slap a patch on them and move on. I love that about her, annoying as she is at the moment. I’ve always been the one who cares too much what the mall rats at school say about my sisters’ clothes.

Blue is just starting to notice. It doesn’t matter as much because she’s sophomore-cute in everything. A genius with needle and thread who embroiders most of her clothes by hand when she’s not working on elaborately stitched portraits of the three of us. She only uses floss in every shade of blue imaginable. True to her name. Today, along the collar of her plain white T-shirt, she stitched the words you don’t get to tell me what to do in bright cerulean thread. Blue’s a passive but funny badass who literally wears her heart on her sleeve, or collar, or the back of her coat. Wherever the needle fits.

Five minutes later, Birdie lands with a soft thud in the grass, oiled canvas bag secure on her back, and a sly grin replacing her scowl.

“We’re good. Let’s roll.”

She’s good. Her lack of forethought means I missed the opportunity to give my self-portrait necessary eyes. They’re always the hardest for me to paint. You can read a ton in a person’s eyes and having to say something about my own has been tripping me up. Some days, when I look in the mirror, I see my fears written all over my face. Like someone took my normal expression and turned it into a crumpled bag full of fear that something will happen to my sisters if I’m not watching. Fear that one day we’ll be separated. Fear that the world will end without warning and all the prepping and training we’ve done won’t matter. My eyes are haunted, accented with shadowy crescents. On other days, I’ll gaze at myself in the mirror and see none of those things. Staring back at me is the girl I believe I am. Strong. Capable. Protective. One of a kind.

Blue calls shotgun before we slide into the ancient station wagon Mother argues is vintage. It’s the only car we’ve ever had. I’m glad Birdie is sitting in the back today. Lately, when I’ve gotten mad at her for not being considerate of anyone’s time but her own, I’ve let my mouth say things I don’t mean before my brain catches up. I hate myself when that happens, because any day could be the one that changes everything.

Today is as good a day as any.

A musky smell wafts over to me when I start the engine. The vanilla, tree-shaped air freshener hanging from the rearview mirror isn’t covering the stench of goat fur rising off Blue’s clothes.

“Did you lay down with the goats when you milked them this morning?”

She shrugs one shoulder. “If I don’t, who will?”

“They’re not pets, Blue. Especially the buck. Someday we may have to eat them.”

“Goat jerky for everyone,” Birdie chirps from the back.

I flick hawkish eyes to the rearview. It would be a last resort, but she’s not helping.

“They’re pets to me,” Blue says. “I’d rather die than eat them.”

“Don’t say that.”

“Well, if Mother would let us have a dog, maybe I wouldn’t need to play with the goats as much.”

“You have Achilles. He’s better than any dog.”

“I still want one. Golden with a black muzzle. I’d name him Banjo.”

Mother claims she’s allergic to cats and dogs. She can’t be near the rabbits, either, even though we breed them for meat. But Achilles is a peregrine falcon. Birdie found him in the woods while she and Mother were hunting, his foot all tangled up in fishing line one of the Burrow Boys left near the lake. She brought him home, even though he was scared and bit Birdie’s hand so deep she needed five stitches. Blue offered to take over his care while her stitches healed, and once Blue and Achilles bonded it was bye-bye Birdie.

He has one lame claw, but that doesn’t stop him from doing anything. He just favors his left talons. Everyone else in our coalition is cautious of Achilles, just because of the one time he scared Tashi Garcia’s little brother Tito so bad he peed his pants. If you ask me, Tito had it coming. That’s what he gets for trying to take the pheasant Achy caught himself for dinner. Believe me, there are days after training where I’m hungry enough to make any boy dumb enough to try and take my supper pee his pants too. Fair is fair.

The best thing about Achilles, though, is he’ll do the killing Blue won’t. That and the little leather hood he wears. You have to see it to believe it. The goats are cool, and the does are ridiculously cute, but my sister really does have the most kickass pet in The Nest. Maybe the state.

It’s too late to have her change, so I toss her the hand sanitizer we keep in the wagon’s ashtray. “Open your window and air yourself out.”

I look at Birdie one more time and see her rummaging through her EDC. I hope she’s making sure she has everything she needs because there’s no way I’m turning around.

I charge down the dirt road to the main, kicking up dust like the riffraff everybody at school imagines we are. In a couple of miles we pass Tashi Garcia’s house, followed by Camilla Clarke’s, then Annalise Ackerman’s, and all the other Nest households. We turn left, away from the road that leads to The Burrow. I spy Birdie staring longingly in hopes of seeing Daniel Dobbs. The lovestruck subordinate dressed in thrift store fatigues from the local AMVETS that’s become my sister’s soul focus. That’s not a misnomer.

At school we’ll go our separate ways, to classes in different parts of the building, passing each other in the hallways here and there. But I know where my sisters are at all times. I know every exit, entrance, and access point to the school. And so do they. Sometimes, one or more Nesters or Burrowers pull out ahead or behind us and we’ll drive to school like a caravan of outcasts. Ripe for being ostracized by people who think the brands of makeup or clothing they wear are their biggest obstacle to survival. For them, they probably are. Surviving high school is as far and wide into the future as they can think. Not that it matters. Today is a good mirror day.

We can handle them. My sisters and I can handle anything.

Copyright © 2020 Demetra Brodsky