Some writers dream of their words bound up in print. Some long to see their worlds on the silver screen. Debut author Robert Cochran is one of the lucky ones who’s got it both ways.

Some writers dream of their words bound up in print. Some long to see their worlds on the silver screen. Debut author Robert Cochran is one of the lucky ones who’s got it both ways.

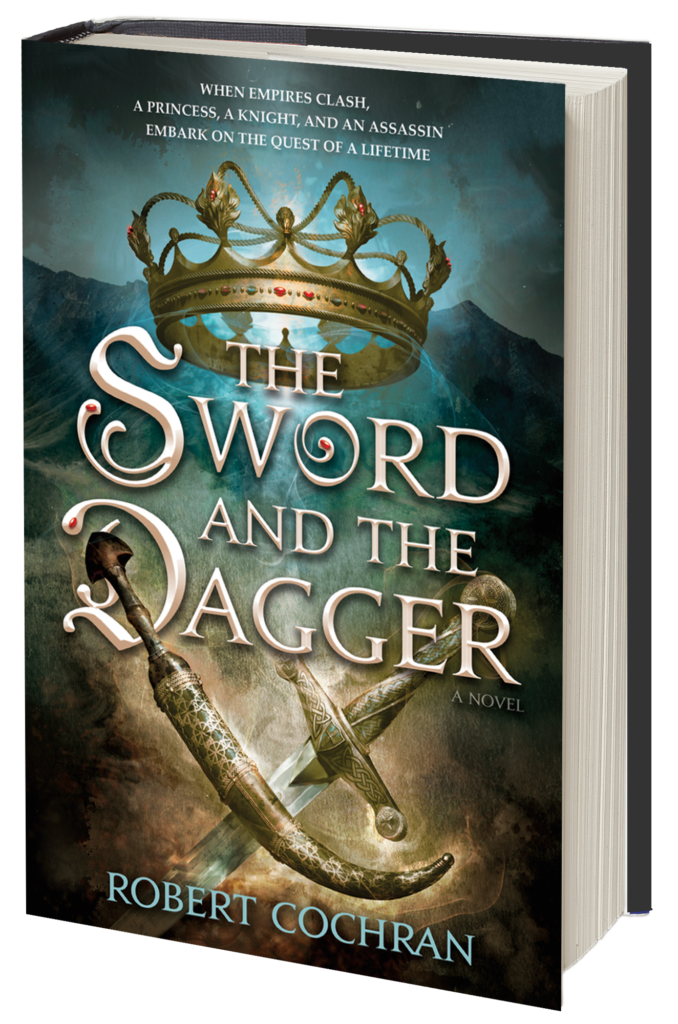

Robert Cochran is an Emmy Award-winning executive producer and showrunner who co-created and executive produced the international television series phenomenon 24 and 24: Live Another Day. Cochran’s first novel, The Sword and the Dagger, is an epic YA tale of adventure and romance about three young people who must grapple with fundamental issues of loyalty, friendship, faith, honor, and courage against the backdrop of conflicts that still resonate today.

Below he shares the three challenges he faced transitioning from screen to page and how he overcame them. The Sword and the Dagger is on sale on April 9.

—

Written by Robert Cochran

I’ve spent most of my career writing screenplays (mostly television, for shows such as The Commish, JAG, La Femme Nikita, and 24). In fact, I’d originally intended to write The Sword and the Dagger as a movie script, but I soon came to the conclusion that the scope of the story was better suited to a novel, and so I decided to write one. It was quite an adventure!

The two forms have much in common both require a strong story, compelling characters, and realistic dialogue – but there are also some differences. Here are a few of them.

WORDS vs. PICTURES

Obviously, film is primarily visual. After all, the first movies were “silent films,” and it’s been said that even today an audience should be able to follow the general outline of the story without dialogue (nobody says, “Hey, let’s go hear a movie!”). The great advantage of film is that a huge amount of information can be conveyed by a shot lasting only a few seconds information not only about the physical setting but also about the characters: their age, appearance, dress, race, social status, etc. All this and more is apparent in an instant or two; even their moods and feelings can be shown through facial expressions and body language all without a word being spoken.

By contrast, in a novel, you must use words to paint the picture that a camera could show in an instant. Take the first chapter in The Sword and the Dagger. It’s set in the garden of a medieval castle in the Middle East during the 13th century. Obviously, ruins aside, I’d never seen a medieval castle (certainly not during the 13th century!) and a lot of questions arose, such as: What would the weather be like? What foliage would be in the garden? What’s the general layout and appearance of the castle? What kind of people would be there and what would they be doing and wearing? Would they be armed, and with what weapons? The setting had to be described in enough detail to be convincing, but not so much as to be boring. Hours of research were required just to set the scene for the first chapter; the hardest part was settling on the right details the ones that would be most vivid and make the setting come alive for the reader. The details need not only be visual but should include all the senses smell, sound, touch, taste whatever works best in the scene.

That’s if you’re writing a novel. If you’re writing a screenplay, on the other hand, here’s what you do. You open up your scriptwriting program and type the following:

EXT. CASTLE GARDEN, 1220 – DAY

And you’re pretty much finished.

Okay, I’m exaggerating a bit. But the point is that in the movies (or television), you have a crew of dozens of Department Heads and their assistants who, under the supervision of the director and producer(s), will deal with the questions mentioned above. As a screenwriter you have to do enough research to avoid making silly mistakes but the amount of detail you must know is pretty modest. As a novelist, you don’t have Department Heads, you are the Department Heads – all of them. You are the director, producer, production designer, Art Department, Wardrobe Department, Prop Department, Makeup Department, Casting Department, Stunt Department and every other department, for every single page of the novel.

Historical novels are extreme cases because considerable research is always necessary. A modern police procedural or thriller would probably require less research, and a family drama might require very little. But in all cases you have to provide enough details – the right details – to draw the reader into the story, whether from research or your imagination or (almost always) a combination of both.

INNER MONOLOGUE

The great advantage of a novel is that you can get inside a character’s head, and show exactly what he or she is thinking and feeling. A character’s backstory, through memories, can be accessed the same way. Now, you can’t do too much of this – my tendency at first was to tell the reader what all the characters were thinking all the time, but this becomes tedious and slows the story down; action and dialogue are important in novels, just as they are on screen. In fact, even in a novel often the most effective way to reveal what a character is feeling or thinking is by describing what they do or say. Still, a novel generally does allow you to delve more deeply and intimately into a character’s inner life; in fact, the readers of a well-written novel probably know the characters in the book better than they know most of their friends in in real life!

To a certain extent, film can also go “interior,” through narration and voiceover. But these have to be used sparingly, otherwise they can become distracting and even irritating. Also, it’s important to point out that good screenwriting, coupled with good acting, can do much to reveal a character’s innermost thoughts, and the best movies and television shows certainly do depend on exploration of character. Nevertheless, film, even with excellent writing and acting, can rarely examine character with quite the same depth, precision, and intimacy as a novel.

STORY COMPRESSION

Movies last two hours, give or take, and this forces a certain compression in storytelling – fewer characters, sparser dialogue, tighter and more structured storylines. There’s less time for diversions, for exploring the nuances of character, or developing emotional or psychological themes. You often see references to “sprawling novels,” but rarely to a “sprawling movie;” a movie that “sprawls” is likely to seem incoherent and unfocused. Television, especially network television, is even more tightly structured; episodes must be timed to the second and must accommodate several commercial breaks as well. Much has to be implied rather than explored.

The recent advent of streaming has challenged these limitations. Traditionally, TV shows have been written while in production – that is, some episodes are being written or produced at the same time that earlier episodes are being aired. Streamed shows, often designed for binge-watching, are written in advance, before filming starts. This gives the writers more breathing room and enables them to “decompress” the stories. The writers can plan out an entire season and make the episodes flow into each other seamlessly, developing characters and themes in more novelistic ways. Whether such shows can truly equal the depth of novels is an open question, but the better ones are certainly making a very strong effort.

WHICH IS HARDER – SCREENPLAYS OR NOVELS?

They’re both hard! In the early and mid-20th century, when movies were still a (relatively) new art form, a number of famous novelists, including such titans as F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner, tried their hand at screenwriting without much success, suggesting that the two forms have skill sets that don’t overlap. But since that time, this distinction, if it ever really existed, has faded and many writers have excelled in both forms – George R. R. Martin, Joan Didion, David Benioff, Gillian Flynn, and the late William Goldman to name just a very few. As long as the writer keeps in mind the relative strengths and weaknesses of each form, there’s no need to choose!