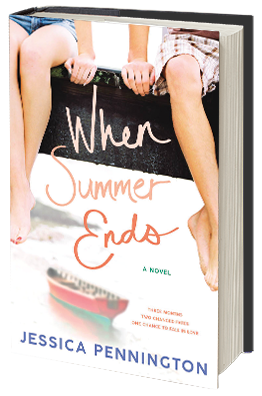

Two teenagers discover how an unexpected turn of fate can bring new love to heal old wounds in Jessica Pennington’s stunning, romantic YA novel When Summer Ends.

Aiden Emerson is an all-star pitcher and the all-around golden boy of Riverton. Or at least he was, before he quit the team the last day of junior year without any explanation. How could he tell people he’s losing his vision at seventeen?

Straight-laced Olivia thought she had life all figured out. But when her dream internship falls apart, her estranged mother comes back into her life, and her long-time boyfriend ghosts her right before summer break, she’s starting to think fate has a weird sense of humor.

Each struggling to find a new direction, Aiden and Olivia decide to live summer by chance. Every fleeting adventure and stolen kiss is as fragile as a coin flip in this heartfelt journey to love and self-discovery from the author of Love Songs & Other Lies.

Chapter 1

Aiden

[dropcap type=”circle”]J[/dropcap]ust put it in his mitt, and you can get off of this field. When I stand on the mound, that’s what I think about now. When I’m standing on the mound, or sitting in the dugout with moon dust caked on my pants. Or when I’m riding my bike, wishing I were still behind the wheel of my car. I played summer league when I was a kid, and I don’t remember wanting to get of of the mound as badly as I do now. I’d think about the way the sweat and dirt would make my face red and scratchy. How the short stocky kid who played right field always lost his white uniform socks and would come in his dad’s black dress socks. When I was twelve, I’d think about impressing the girls who had come to watch us play. Or I’d think about the motions I was about to go through. About how I needed to present the ball for just long enough. Shifting my weight at the right moment, squaring up to the batter after releasing the ball. I don’t remember my dad’s yelling back then, but I’m sure it was always there, like a soft static that was drowned out by all of the other thoughts. The girls and the pizza after the game were louder than he was.

[dropcap type=”circle”]J[/dropcap]ust put it in his mitt, and you can get off of this field. When I stand on the mound, that’s what I think about now. When I’m standing on the mound, or sitting in the dugout with moon dust caked on my pants. Or when I’m riding my bike, wishing I were still behind the wheel of my car. I played summer league when I was a kid, and I don’t remember wanting to get of of the mound as badly as I do now. I’d think about the way the sweat and dirt would make my face red and scratchy. How the short stocky kid who played right field always lost his white uniform socks and would come in his dad’s black dress socks. When I was twelve, I’d think about impressing the girls who had come to watch us play. Or I’d think about the motions I was about to go through. About how I needed to present the ball for just long enough. Shifting my weight at the right moment, squaring up to the batter after releasing the ball. I don’t remember my dad’s yelling back then, but I’m sure it was always there, like a soft static that was drowned out by all of the other thoughts. The girls and the pizza after the game were louder than he was.

But now, standing on the mound, the ball sticky in my hand, all I hear is my father, saying out loud all of the things I’m thinking. He’s standing behind the fence next to the dugout, his brow almost as wet as mine. At least mine is hidden by my Hornets hat. His is shining red, matted with damp brown hair.

“One more, Emerson!” he screams, his voice getting a little hoarse from the last eight innings. “Make it count!”

The ball leaves my hand and I can feel the verdict before the plate ump delivers it. “Ball two!”

My father’s hands slam against the wire cage in front of him. “No! Head in the game! You’ve got this, Emerson!”

There’s something really weird about my dad calling me by my last name. I think it’s a habit that carried over from little league, when he was my coach and wanted to treat me like the rest of the team. I can’t blame my dad for yelling today. He’s just saying out loud what I’m thinking:

What are you doing, Aiden?

Focus!

Get this over with already!

I’m the fastest pitcher in our district, by just one percent. And if I could simply focus do what my dad is begging of me this game could be over.

Focus, focus, focus. I squint my eyes against the glare of the sun, and cock my head to the side. Better.

I wipe my fingers down the side of my blue pants and pat my palm against my thigh. Left. Right. I crank my neck back and forth, as if that’s going to fix the knot in my arm, the pain in my head, or the real problem the blurriness as I stare straight ahead at the worn brown glove of my catcher, Zander. He’s clad in black and blue gear, flashing me a two, then four, then two, with his fingers between his knees. Two is my curve ball, and I shake my head at him, telling him it’s a no-go. I don’t trust myself today. He flashes it again and jerks his mitt to where he wants the ball, close and inside.

“Two up, two down!” Mani, our shortstop shouts to our teammates, letting them know we’re going to get these next two outs. We’re up by one with runners on first and second, in our last game of the regular season. The last win we need to take us into regionals. Back-to-back-to-back titles could be ours.

I bring the ball to my chest and feel the power charge through me as I release it toward the plate. I can feel that one percent. Feel it racing through my arm, feel it slip past my fingertips. This. Is

I hear the unmistakable groan as leather meets skin. A grunt, a lurch, as the batter crumples to the ground, the ball falling of of his bicep down to the plate.

The ump stands. “Take your base,” he yells in a booming voice. There’s a special tone that umps save for pitchers who hit batters. There’s always a warning to that particular command: Don’t do it again.

“Emerson!” my dad yells, the metallic clang of the fence in harmony with him. His voice has an edge of knowing sympathy. “It’s just muscle memory! Focus!”

Zander throws his face guard back and puts his hands in a T over his head as he trots out to the mound. I jab my toe into the hard dirt.

“Shake it off, bud.”

Despite his best eforts, Zander and I really aren’t buds. We’re more of a codependent two-person ecosystem. Without me, he can’t do his job. He can’t be amazing until I am. You can be an amazing catcher, but without the right pitcher, you’re just catching the ball. With a bad pitcher, you’re chasing the ball.

He grabs my head in his hands and pulls it toward him. Zander loves these big shows. The whispers of, “Look at him, bringing Emerson back down, getting him focused.” People love the idea that we’re some sort of dynamic duo, on the field and of. “Shake it of. He had it coming. He leaned into it, man.” I know he didn’t, I know I was of, too tight, too wild. I shouldn’t have tried for inside. I told Zander. I don’t say it, because this is a show, not a conversation. “You’ve got this next guy. You hold them here.” I twist my head and pull away—I don’t like his little shows. I nod, because I know he won’t let up until I do.

My best chances for a strikeout are now on first, second, and third, and the top of the lineup is striding out to home plate. He stops behind the plate, rolls up his sleeve, and pats his bicep. He’s inviting me to hit him, egging me on, mocking me. The all-state pitcher who just nailed a batter. All they need is one run and it’s over. I grit my teeth, and remember what my dad said.

Muscle memory, muscle memory, muscle memory.

I lock my eyes on Zander’s mitt and lean back. I try to relax, let my arms and legs do their thing. The same thing they’ve done for the last ten years. Thousands of batters, tens of thousands of pitches, probably.

I let the sticky leather roll around in my hand, squeeze it tight, and let it roll of the tips of my fingers. When I was a kid, I had to remind myself what to do after the ball left my hand. I’d count it out step by step: present…cock…knee up…release… pivot . . . so much of it is natural momentum. But at the end, when you bring your body back to the center, position your glove in front of you, and stand ready that takes thought. But even that is muscle memory now. I’m not even thinking as I let my weight shift to my left leg; as my right comes down and swings to the side. There are no thoughts as my glove comes up to my chest and my leg pivots out. Not a single thought as the white blur of leather leaves the bat and makes contact with my face. No thoughts as I hit the ground, my mother’s shriek hanging in the air.

Copyright © 2019 Jessica Pennington