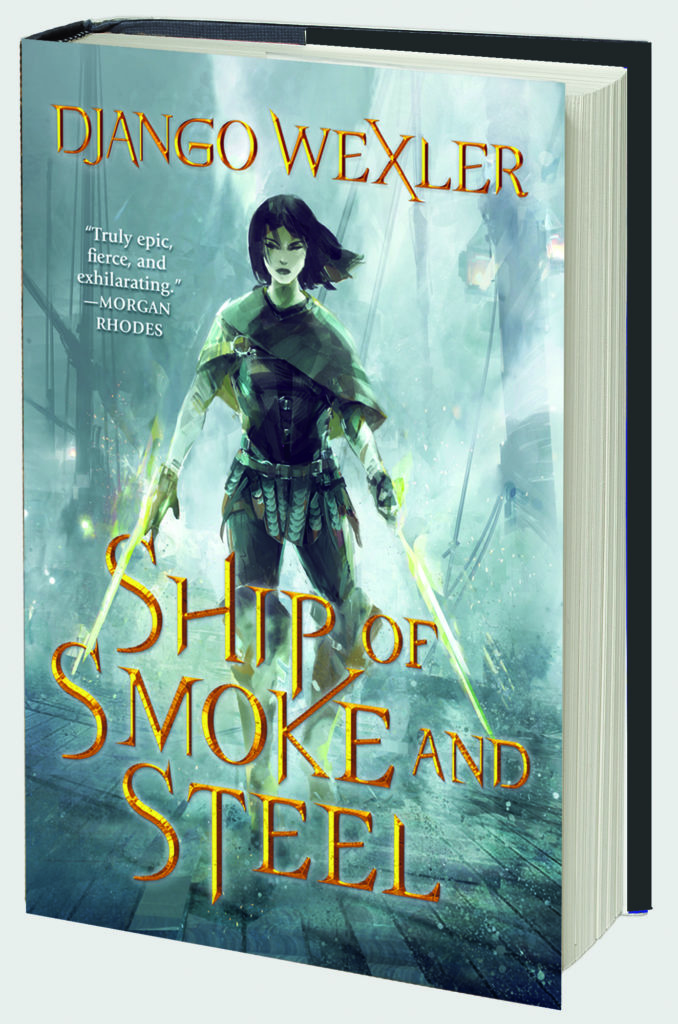

Ship of Smoke and Steel is the launch of Django Wexler’s cinematic, action-packed epic fantasy Wells of Sorcery trilogy.

In the lower wards of Kahnzoka, the great port city of the Blessed Empire, eighteen-year-old ward boss Isoka enforces the will of her criminal masters with the power of Melos, the Well of Combat. The money she collects goes to keep her little sister living in comfort, far from the bloody streets they grew up on.

When Isoka’s magic is discovered by the government, she’s arrested and brought to the Emperor’s spymaster, who sends her on an impossible mission: steal Soliton, a legendary ghost ship—a ship from which no one has ever returned. If she fails, her sister’s life is forfeit.

On board Soliton, nothing is as simple as it seems. Isoka tries to get close to the ship’s mysterious captain, but to do it she must become part of the brutal crew and join their endless battles against twisted creatures. She doesn’t expect to have to contend with feelings for a charismatic fighter who shares her combat magic, or for a fearless princess who wields an even darker power.

Excerpt

[dropcap type=”circle”] E [/dropcap]veryone has their addictions.

[dropcap type=”circle”] E [/dropcap]veryone has their addictions.

Mine isn’t drink, or dice, or sex. That’s not to say I never have a jug or three, or that I’m immune to the rush of clinking coin and clattering bone, or that I’ve never spent the evening in the company of a pretty boy from Keyfa’s brothel. But these are things I could do without, if I had to.

My addiction is Tori. I can no more stay away from her than a plant can turn away from the sun.

Hagan picks me up after breakfast, at a suitably discreet spot far from our usual haunts. He’s driving a battered old cab, with proper livery and permits. Nothing fake—I have an arrangement with the owner, and he keeps Hagan’s name on the books as a licensed driver. Hagan dresses the part, too, in a cabdriver’s shabby linen and slouching felt cap. The elderly mare in the traces gives a snort at the sight of me, and her ears flick while I climb aboard.

Then it’s up to the Second Ward, up the great hill, climbing away from the sea and out of the miasma of smoke and poverty. It’s like ascending the celestial mountain where the Blessed One dwells with the heavenly court. Except at the top of our mountain sit the nobles and the Emperor’s favorites—more like rotspawn, in other words, than choirs of angels. We drive through the main gate under the suspicious eye of the Ward Guard, but our passes are in order, and a few coins encourage him not to ask unnecessary questions.

Hagan knows the routine, and he drives in silence. I’m back in my kizen, ridiculous, tight-bound thing, trying to look like the respectable lady I’m not. I don’t know why I bother. It never works.

***

The house is beautiful, all wide porches, gently sloped roofs in elegant gray-green tile, manicured lawns, and a tiny, perfect pond. I stand outside, about as welcome as a dead dog floating in that pond. I can see it on the faces of the servants, when they think I’m not looking. The gardener in his broad straw hat stares at me and spits in the grass; the doorman’s hand hovers near his sword as he lets me through the front door. A young woman brings me tea, moving with grace in spite of her restrictive kizen. She places the cup in my hand as courtesy demands but carefully avoids even the slightest brush against my skin. Then she hurries off, no doubt to wash thoroughly.

None of them know who I really am, of course. To them I’m just a strange visitor their mistress inexplicably tolerates, reeking of the dung of the lower wards. If they knew the truth, they’d be less polite.

The Rot can take all of them. They’re not the ones I’m here to see.

After letting me cool my heels in the waiting room for a few minutes, another footman arrives to escort me to the inner garden. This is a private space at the very center of the house, stone walled and ringed by tall, drooping willow trees. Only a few trusted servants are allowed here. They know that my gold pays their wages and puts food on their tables—though even the most trusted don’t know where that gold comes from, of course—and they’ve been warned, discreetly, of the consequences should any of this information be revealed.

They are considerably more respectful.

Ofalo greets me at the garden gate. He’s an old man, balding and long bearded, like a statue of the Blessed One. He bows low, and I wave at him to get on with it.

Addiction. I’ve spent too much time here already. I shouldn’t be here at all. Every minute is a risk. Every minute is weakness. Every time I leave I swear I won’t come back, that next time I’ll send some go-between who knows nothing and endangers nothing. Just knowing that this place is here should be enough, but it’s not. I have to see her smile, or I start to feel hollowed out. I start to think dangerous thoughts.

“Welcome, Lady Isoka,” Ofalo says. “Lady Tori will be here any moment.”

“Good. Anything I need to know?”

If Ofalo objects to being snapped at by a girl of eighteen, he doesn’t show it. That’s one of the reasons I like him. He’s been my factor here since the beginning, and he’s never given me cause to regret it, never asked too many questions. Blessed knows I pay him enough.

“No, my lady. A few trivial disputes among the staff. Nothing that requires your attention.”

“Anyone who troubles Tori is to be turned out immediately.”

“Of course, my lady.” Ofalo bows again. “Shall I send for refreshments?”

“No.” I grit my teeth. “I’m not staying long.”

“As you say.”

He bows again and withdraws on noiseless feet. I go into the garden and sit at the little stone table, staring down at the tiny babbling brook. It’s perfect, the epitome of everything a brook should be. Someone made it that way, placed every stone with careful consideration, taking into account the sound of the water and the way the light filters through the willows. The whole house is like that, smooth and deliberate, a work of art.

It’s another reason I can’t stay here too long. It makes me want to break something.

Tori moves so gracefully I don’t even notice when she comes in. She’s wearing a light blue kizen, fading to purple at the bottom, like a clear sky passing slowly from day to twilight. I can’t stand the things. I hate the way they restrict me to tiny, mincing steps and pin my arms to my sides. But Tori wears hers effortlessly, as though she were born to it, as elegant at thirteen years old as any lady of the Imperial court.

We don’t look much like sisters. We’re both short, though she’s still growing and she’ll soon be taller than me. We have the same straight, dark hair, but mine is cut short and tied up, while hers falls like a black curtain to her waist, thick and glossy as a waterfall of ink. Her skin is smooth, her hands uncallused. She’s so beautiful it makes me want to weep. And when she sees me, her face lights up, and I realize all over again why I can’t stop coming here.

“Isoka!” She runs to me, as fast as the restrictive kizen will allow, all her decorum forgotten. I love her for that, too. She throws her arms around me and I hug her back. “It’s been so long,” she says. “I thought you’d forgotten about me.”

“I know.” Three months. Longer than ever before, weaning myself off her like an addict trying to get clean of dream-smoke. “I’m sorry. I’ve been busy.”

“Are you going to be staying tonight?” Tori says. “I’ll get Viala to make something special—”

“No!” I blurt out. “I’m sorry, Riri. I don’t have long.”

Her face falls, but there’s still a hint of a smile at the pet name. She’s too old for it. Another few years and she’ll be something like a woman. I find it hard to imagine.

“Before I go,” I say, “I need you to tell me everything that’s been happening. I rely on you to keep an eye on things, you know.”

That’s all it takes to get her smiling again. She sits across from me and launches into a story about the cook’s dog getting into trouble. I listen and make encouraging noises, and just watch her. Remember this, I tell myself, over and over. Save this, for when you need it.

“Isoka,” she chides. “You’re not listening.”

“Sorry.” I shake my head. “What happened to the dog?”

“Old Mirk only has three teeth left, poor thing. Last month Narzo said he wasn’t good for anything and wanted to put him down, but I wouldn’t let him. You can’t get rid of someone just because they aren’t useful anymore.”

“That was very kind of you.”

Her face clouded. “He died anyway, though. Last week. Tutor says that’s the way of nature and I shouldn’t be sad about it, but I cried anyway.”

My sister, who cares for worn-out dogs and other broken things. I see Shiro’s face, his last shudder, and my throat goes tight. Tori’s a hundred times better than me, and if the only thing I do with my life is make sure she stays that way, it’ll have been enough. Someday she’ll be grown, and she’ll have enough money that she’ll never have to work, or to marry if she doesn’t want to. She won’t remember huddling under the bushes in the public gardens when it rained, or dodging the kidcatchers who snatch little girls for the dockside brothels.

“. . . and when I told Garalo about it,” she’s saying, “he said that’s the same way the nobility treat the common folk, working them to the bone and then throwing them away. I said they shouldn’t be allowed to, and—”

“Wait.” I fix her with a look. “Who’s Garalo?”

“Just a boy I know.” Tori’s guilty look is blindingly obvious on her guileless face. “I talk to him in the market sometimes.”

“How did you meet him?”

“Kuko wanted to listen to a speech, so she took me after shopping. Then I had questions, so we stayed and got to talking.”

“Tori . . .” I take a breath.

“I know,” she says. “I have to be careful. I’m not a baby, Isoka. Garalo talks to lots of people.”

“It’s still not safe to get involved in politics,” I tell her. “You never know what kind of attention that’s going to attract.”

“But—”

“You have everything you need right here, don’t you?” I venture a smile. “Don’t go looking for trouble.”

Tori looks away for a moment, and I think she’s going to argue. Then the tension goes out of her, and she nods. I lean forward and wrap her in a hug, remembering the little girl who clung to my side when we huddled in the gutter.

I’m getting dirty, I want to tell her, so you can stay clean. But she can’t know that.

Copyright © 2019 by Django Wexler