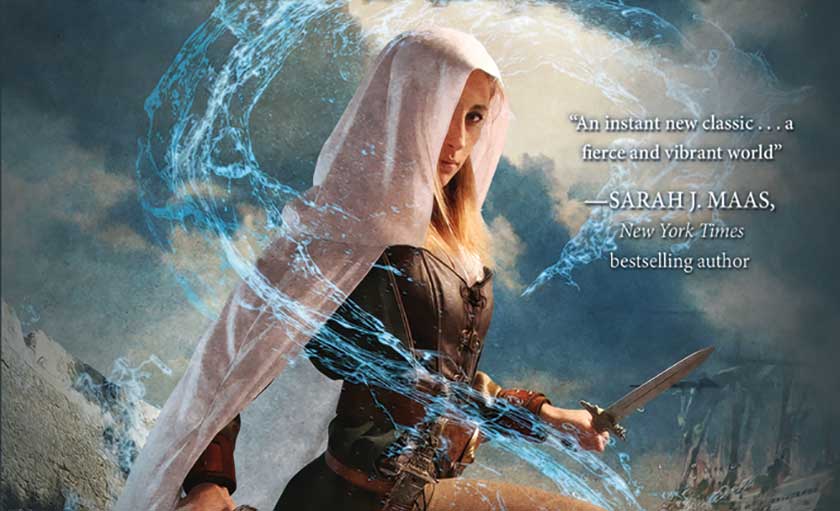

In the Witchlands, there are almost as many types of magic as there are ways to get in trouble—as two desperate young women know all too well.

Safiya is a Truthwitch, able to discern truth from lie. It’s a powerful magic that many would kill to have on their side, especially amongst the nobility to which Safi was born. So Safi must keep her gift hidden, lest she be used as a pawn in the struggle between empires.

Iseult, a Threadwitch, can see the invisible ties that bind and entangle the lives around her—but she cannot see the bonds that touch her own heart. Her unlikely friendship with Safi has taken her from life as an outcast into one of reckless adventure, where she is a cool, wary balance to Safiya’s hotheaded impulsiveness.

Safiya and Iseult just want to be free to live their own lives, but war is coming to the Witchlands. With the help of the cunning Prince Merik (a Windwitch and privateer) and the hindrance of a Bloodwitch bent on revenge, the friends must fight emperors, princes, and mercenaries alike, who will stop at nothing to get their hands on a Truthwitch.

ONE

[dropcap type=”circle”]E[/dropcap]verything had gone horribly wrong.

None of Safiya fon Hasstrel’s hastily laid plans for this holdup were unfolding as they ought.

First, the black carriage with the gleaming gold standard was not the target Safi and Iseult had been waiting for. Worse, this cursed carriage was accompanied by eight perfect rows of city guards blinking midday sun from their eyes.

Second, there was absolutely nowhere for Safi or Iseult to go. Up on their limestone outcropping, the dusty road below was the only path to Veñaza City. And just as this craggy thrust of gray rock overlooked the road, the road overlooked nothing but turquoise sea forever. It was seventy feet of cliff pounded by rough waves and even rougher winds.

And third—the real kick in the kidneys—was that as soon as the guards marched over the girls’ buried trap and firepots within exploded … Well, then those guards would be scouring every inch of the cliffside.

“Hell-gates, Iz.” Safi snapped down her spyglass. “There are four guards in each row. Eight times four makes…” Her face scrunched up. Fifteen, sixteen, seventeen …

“It’s thirty-two,” Iseult said blandly.

“Thirty-two thrice-damned guards with thirty-two thrice-damned crossbows.”

Iseult only nodded and eased back the hood of her brown cape. The sun lit up her face. She was the perfect contrast to Safi: midnight hair to Safi’s wheat, moon skin to Safi’s tan, and hazel eyes to Safi’s blue.

Hazel eyes that were now sliding to Safi as Iseult plucked away the spyglass. “I hate to say ‘I told you so’—”

“Then don’t.”

“—but,” Iseult finished, “Everything he said to you last night was a lie. He was most certainly not interested in a simple card game.” Iseult ticked off two gloved fingers. “He was not leaving town this morning by the northern highway. And I bet”—a third finger unfurled—“his name wasn’t even Caden.”

Caden. If … no, when she found that Chiseled Cheater, she was going to break every bone in his perfect rutting face.

Safi groaned and banged her head against the rock. She’d lost all of her money last night. Not just some, but all.

Last night had hardly been the first time Safi had bet all of her—and Iseult’s—savings on a card game. It wasn’t if she ever lost, for as the saying went, You can’t trick a Truthwitch.

Plus, the winnings off one round alone from the highest-stake taro game in Venaza City would have bought Safi and Iseult a place of their own. No more living in an attic for Iseult, no more stuffy Guildmaster’s guest room for Safi.

But as Lady Fate would have it, Iseult hadn’t been able to join Safi at the game—her heritage banned her from the highbrow inn where the game had taken place. And without her Threadsister beside her, Safi was prone to … mistakes.

Particularly mistakes of the strong-jawed, snide-tongued variety who plied Safi with compliments that somehow slipped right past her Truthwitchery. In fact, she hadn’t sensed a lying bone in Chiseled Cheater’s body when she’d collected her winnings from the in-house bank … Or when Chiseled Cheater had hooked his arm in hers and guided her into the warm night … Or when he’d leaned in close for a chaste yet wildly heady kiss on the cheek.

I will never gamble again, she swore, her heel drumming on the limestone. And I will never flirt again.

“If we’re going to run for it,” Iseult said, interrupting Safi’s thoughts, “then we need to do so before the guards reach our trap.”

“You don’t say.” Safi glared at her Threadsister, who watched the incoming guards through the spyglass. Wind kicked at Iseult’s dark hair, lifting the wispy bits that had fallen from her braid. A distant gull cried its obnoxious scree, scr-scree, scr-scree!

Safi hated gulls; they always shit on her head.

“More guards,” Iseult murmured, the waves almost drowning out her words. But then louder, she said, “Twenty more guards coming from the north.”

For half a moment, Safi’s breath choked off. Now, even if she and Iseult could somehow face the thirty-two guards accompanying the carriage, then the other twenty guards would be upon them before they could escape.

Safi’s lungs burst back to life with a vengeance. Every curse she’d ever learned rolled off her tongue.

“We’re down to two options,” Iseult cut in, scooting back to Safi’s side. “We either turn ourselves in—”

“Over my grandmother’s rotting corpse,” Safi spat.

“—or we try to reach the guards before they trigger the trap. Then all we have to do is brazen our way through.

Safi glanced at Iseult. As always, her Threadsister’s face was impassive. Blank. The only part of her that showed stress was her long nose—it twitched every few seconds.

“Once we’re through,” Iseult added, drawing her hood back into place and casting her face in darkness, “we’ll follow the usual plan. Now hurry.”

Safi didn’t need to be told to hurry—obviously she would hurry—but she bit back her retort. Iseult was, yet again, saving their hides.

Besides, if Safi had to hear one more I told you so, she’d throttle her Threadsister and leave her carcass to the hermit crabs.

Iseult’s feet hit the gritty road, and as Safi descended nimbly beside her, dust plumed around her boots—and inspiration struck.

“Wait, Iz.” In a flurry of movement, Safi swung off her cape. Then with a quick slash-rip-slash of her parrying knife, she cut off the hood. “Skirt and kerchief. We’ll be less threatening as peasants.”

Iseult’s eyes narrowed. Then she dropped to the road. “But then our faces will be more obvious. Rub as much dirt on as you can.” As Iseult scrubbed her face, turning it a muddy brown, Safi tied the hood over her hair and wrapped the cape around her waist. Once she’d tucked the brown cloak into her belt, careful to hide her scabbards beneath, she too slathered dirt and mud over her cheeks.

In less than a minute, both girls were ready. Safi ran a quick, scrutinizing eye over Iseult … but the disguise was good. Good enough. Her Threadsister looked like a peasant in desperate need of a bath.

With Iseult just behind, Safi launched into a quick clip around the limestone corner, her breath held tight … Then she exhaled sharply, pace never slowing. The guards were still thirty paces from the buried firepots.

Safi flashed a bumbling wave at a mustached guard in the front. He lifted his hand, and the other guards came to an abrupt stop. Then, one by one, each guard’s crossbow leveled on the girls.

Safi pretended not to notice, and when she reached the pile of gray pebbles that marked the trap, she cleared it with the slightest hop. Behind her, Iseult made the same, almost imperceptible leap.

Then the mustached man—clearly the leader—raised his own crossbow. “Halt.”

Safi complied, letting her feet drag to a stop—while also covering as much ground as she could. “Onga?” she asked, the Arithuanian word for yes. After all, if they were going to be peasants, they might as well be immigrant peasants.

“Do you speak Dalmotti?” the leader asked, looking first at Safi. Then at Iseult.

Iseult came to a clumsy stop beside Safiya. “We spwik. A litttttle.” It was easily the worst attempt at an Arithuanian accent that Safiya had ever heard from Iseult’s mouth.

“We are … in trouble?” Safi lifted her hands in a universally submissive gesture. “We only go … to Veñaza City.”

Iseult gave a dramatic cough, and Safi wanted to throttle her. No wonder Iz was always the cutpurse and Safi the distraction. Her Threadsister was awful at acting.

“We want a city healer,” Safi rushed to say before Iseult could muster another unbelievable cough. “In case she has the plague. Our mother died from it, you see, and ohhhh, how she coughed in those final days. There was so much blood—”

“Plague?” the guard interrupted.

“Oh, yes.” Safi nodded knowingly. “My sister is very ill.”

Iseult heaved another cough—but this one was so convincing, Safi actually flinched … and then hobbled to her. “Oh, you need a healer. Come, come. Let your sister help you.”

The guard turned back to his men, already dismissing the girls. Already bellowing orders, “Back in formation! Resume march!”

Gravel crunched; footsteps drummed. The girls trudged onward, passing guards with wrinkled noses. No one wanted Iseult’s “plague” it would seem.

Safi was just towing Iseult past the black carriage when its door popped wide. A saggy old man leaned his scarlet-clad torso outside. His wrinkles shook in the wind.

It was the leader of the Gold Guild, a man named Yotiluzzi, whom Safi had seen from afar—at last night’s establishment, no less.

The old Guildmaster clearly didn’t recognize Safi, though, and after a cursory glance, he lifted his reedy voice. “Aeduan! Get this foreign filth away from me!”

A figure in white stalked around the carriage’s back wheel. His cape billowed, and though a hood shaded his face, there was no hiding the knife baldric across his chest or the sword at his waist.

He was a Carawen monk—a mercenary trained to kill since childhood.

Safi froze, and without thinking, she eased her arm away from Iseult, who twisted silently behind her. The guards would reach the girls’ trap at any moment, and this was their ready position: Initiate. Complete.

“Arithuanians,” the monk said. His voice was rough, but not with age—with underuse. “From what village?” He strolled a single step toward Safi.

She had to fight the urge not to cower back. Her Truthwitchery was suddenly bursting with discomfort—a grating sensation, as if the skin on the back of her neck were being scratched off.

And it wasn’t his words that set Safi’s magic to flaring. It was his presence. This monk was young, yet there was something off about him. Something too ruthless—too dangerous—to ever be trusted.

He pulled back his hood, revealing a pale face and close-cropped brown hair. Then, as the monk sniffed the air near Safi’s head, red swirled around his pupils.

Safi’s stomach turned to stone.

Bloodwitch.

This monk was a rutting Bloodwitch. A creature from the myths, a being who could smell a person’s blood—smell their very witchery—and track it across entire continents. If he latched onto Safi’s or Iseult’s scent, then they were in deep, deep—

Pop-pop-pop!

Gunpowder burst inside firepots. The guards had hit the trap.

Safi acted instantly—as did the monk. His sword swished from its scabbard; her knife came up. She clipped the edge of his blade, parrying it aside.

He recovered and lunged. Safi lurched back. Her calves hit Iseult, yet in a single fluid movement, Iseult kneeled—and Safi rolled sideways over her back.

Initiate. Complete. It was how the girls fought. How they lived.

Safi unfurled from her flip and withdrew her sword just as Iseult’s moon scythes clinked free. Far behind them, more explosions thundered out. Shouts rose up, the horses kicked and whinnied.

Iseult spun for the monk’s chest. He jumped backward and skipped onto the carriage wheel. Yet where Safi had expected a moment of distraction, she only got the monk diving at her from above.

He was good. The best fighter she’d ever faced.

But Safi and Iseult were better.

Safi swooped down and out of reach just as Iseult wheeled into the monk’s path. In a blur of spinning steel, her scythes sliced into his arms, his chest, his gut—and then like a tornado, she was past.

And Safi was waiting. Watching for what couldn’t be real and yet clearly was: every cut on the monk’s body was healing before her eyes.

There was no doubt now—this monk was a thrice-damned Bloodwitch straight from Safi’s darkest nightmares. So she did the only thing she could conjure: she threw her parrying knife directly at the monk’s chest.

It thunked through his rib cage and embedded deep in his heart. He stumbled forward, hitting his knees—and his red eyes locked on Safi’s. His lips curled back. With a snarl, he wrenched the knife from his chest. The wound spurted …

And began to heal over.

But Safi didn’t have time for another strike. The guards were doubling back. The Guildmaster was screaming from within his carriage, and the horses were charging into a frantic gallop.

Iseult darted in front of Safi, scythes flying fast and beating two arrows from the air. Then, for a brief moment, the carriage blocked the girls from the guards. Only the Bloodwitch could see them, and though he reached for his knives, he was too slow. Too drained from the magic of healing.

Yet he was smiling—smiling—as if he knew something that Safi didn’t. As if he could and would hunt her down to make her pay for this.

“Come on!” Iseult yanked at Safi’s arm, pulling her into a sprint toward the cliffside.

At least this was part of their plan. At least this they had practiced so often they could do it with their eyes closed.

Just as the first crossbow bolts pounded the road behind them, the girls reached a waist-high boulder on the ocean side of the road.

They plunked their blades back into scabbards. Then in two leaps, Safi was over the rock—and Iseult too. On the other side, the cliff ran straight down to thundering white waves.

Two ropes waited, affixed to a stake pounded deep into the earth. With far more speed and force than was ever intended for this escape, Safi snatched up her rope, hooked her foot in a loop at the end, gripped a knot at head level …

And jumped.

TWO

Air whizzed past Safi’s ears and up her nose as she sprang out … down toward white waves … away from the seventy-foot cliff …

Until Safi reached the rope’s end. With a sharp yank that shattered through her body and tore into her gripping hands, she flew at the barnacle-covered cliffside.

This was about to hurt.

She hit with a crash, teeth ramming her tongue. Pain sizzled through her body. Limestone cut her arms, her face, her legs. She snapped out her hands to grip the cliff—just as Iseult slammed into the rocks beside her.

“Ignite,” Safi grunted. The word that triggered the rope’s magic was lost in the roar of ocean waves—but the command hit its mark. In a flash of white flame that shot up faster than eyes could travel, their ropes ignited …

And disintegrated. A fine ash kicked away on the wind. A few specks settled on the girls’ kerchiefs, their shoulders.

“Arrows!” Iseult roared, flattening herself against the rock as bolts zipped past. Some skittered off the rocks, some sank into waves.

One sliced through Safi’s skirt. Then she’d managed to dig her toes in cracks, grab for handholds, and scramble sideways. Her muscles trembled and strained until at last, she and Iseult had ducked beneath a slight overhang. Until at last, they could pause and let the arrows fall harmlessly around them.

The rocks were wet, the barnacles vicious, and water swept at the girls’ ankles. Each wave grabbed for them with a crash. Salty drops battered over and over. Until eventually the arrows stopped falling.

“Are they coming?” Safi rasped at Iseult.

Iseult shook her head. “They’re still there. I can feel their Threads waiting.”

Safi blinked, trying to get the salt from her eyes. “We’re going to have to swim, aren’t we?” She rubbed her face on her shoulder; it didn’t help. “Think you can make it to the lighthouse?” Both girls were strong swimmers—but strong didn’t matter in waves that could pummel a dolphin.

“We don’t have a choice,” Iseult said. She glanced at Safi with a fierceness that always made Safi feel stronger. “We can toss our skirts left, and while the guards shoot those, we dive right.”

Safi nodded, and with a grimace, she angled her body so she could remove her skirt. Once both girls had their brown skirts free, Iseult’s arm reared back.

“Ready?” she asked.

“Ready.” Safi heaved. The skirt flew out from beneath the overhang—Iseult’s right behind it.

And then both girls stepped away from the rock face and sank beneath the waves.

As Iseult det Midenzi wriggled free from her sea-soaked tunic, boots, pants, and finally underclothes, everything hurt. Every peeled-off layer revealed ten new slices from the limestone and barnacles, and each burst of spindrift made her aware of ten more.

This ancient, crumbling lighthouse was effective for hiding, but it was inescapable until the tide went out. For now, the water outside was well above Iseult’s chest, and hopefully that depth—as well as the crashing waves between here and the marshy shoreline—would deter the Bloodwitch from following.

The interior of the lighthouse was no larger than Iseult’s attic bedroom over Mathew’s coffee shop. Sunlight beamed in through algae-slimed windows, and wind tugged sea foam through the arched door.

“I’m sorry,” Safi said, her voice muffled as she squirmed from her sodden tunic. Then Safi’s shirt was completely off, and she tossed it on a windowsill. Her usually tanned skin was pale beneath her freckles.

“Don’t apologize.” Iseult gathered her own discarded clothes. “I’m the one who told you about the card game in the first place.”

“This is true,” Safi replied, voice shaking as she hopped on one foot and tried to remove her pants—with her boots still on. She always did that, and it boggled Iseult’s mind that an eighteen-year-old could still be too impatient to undress herself properly. “But,” Safi added, “I’m the one who wanted the nicer rooms. If we’d just bought that place two weeks ago—”

“Then we’d have rats for roommates,” Iseult interrupted. She shuffled to the nearest water-free, sunlit patch of floor. “You were right to want a different place. It costs more, but it would’ve been worth it.”

“Would’ve been being the key words.” With a loud grunt, Safi finally wrestled free of her pants. “There’ll be no place of our own now, Iz. I bet every guard in Veñaza City is out looking for us. Not to mention the…” For a moment, Safi stared at her boots. Then, in a frantic movement, she tore off the right one. “So will the Bloodwitch.”

Blood. Witch. Blood. Witch. The words pulsed through Iseult in time to her heart. In time to her blood.

Iseult had never seen a Bloodwitch before … or anyone with a magic linked to the Void. Voidwitches were just scary stories after all—they weren’t real. They didn’t guard Guildmasters and try to gut you with swords.

After wringing out her pants and smoothing each fold on a windowsill, Iseult shuffled to a leather satchel at the back of the lighthouse. She and Safi always stowed an emergency kit here before a heist, just in case the worst scenario unfolded.

Not that they held many heists. Only a few every now and then for the lowlifes who deserved it.

Like those two apprentices who’d ruined one of Guildmaster Alix’s silk shipments and tried to blame it on Safi.

Or those thugs who’d busted into Mathew’s shop while he was away and stolen his silver cutlery.

Then there were those four separate occasions when Safi’s taro card games had ended in brawls and missing coins. Justice had been required, of course—not to mention reclamation of pilfered goods.

Today’s encounter, though, was the first time the emergency satchel had actually been needed.

After rummaging past the spare clothes and a water bag, Iseult found two rags and a tub of lanolin. Then she hauled up the girls’ discarded weapons and trudged back to Safi. “Let’s clean our blades and come up with a plan. We have to get back to the city somehow.”

Safi yanked off her second boot before accepting her sword and parrying knife. Both girls settled cross-legged on the rough floor, and Iseult sank into the familiar barnyard scent of the grease. Into the careful scrubbing motion of cleaning her scythes.

“What did the Bloodwitch’s Threads look like?” Safi asked quietly.

“I didn’t notice,” Iseult murmured. “Everything happened so fast.” She rubbed all the harder at the steel, protecting her beautiful Marstoki blades—gifts from Mathew’s Heart-Thread, Habim—against rust.

A silence stretched through the stone ruins. The only sounds were the squeak of cloth on steel, the eternal crash of Jadansi waves.

Iseult knew she seemed unperturbed as she cleaned, but she was also absolutely certain that her Threads twined with the same frightened shades as Safi’s.

But Iseult was a Threadwitch, which meant she couldn’t see her own Threads—or those of any other Threadwitch.

When her witchery had manifested at nine years old, Iseult’s heart had felt like it would pound itself to dust. She was crumbling beneath the weight of a million Threads, none of which were her own. Everywhere she looked, she saw the Threads that build, the Threads that bind, and the Threads that break. Yet she could never see her own Threads or how she wove into the world.

So, just as every Nomatsi Threadwitch did, Iseult had learned to keep her body cool when it ought to be hot. To keep her fingers still when they ought to be trembling. To ignore the emotions that drove everyone else.

“I think,” Safi said, scattering Iseult’s thoughts, “the Bloodwitch knows I’m a Truthwitch.”

Iseult’s scrubbing paused. “Why,” her voice was flat as the steel her in hands, “would you think that?”

“Because of the way he was smiled at me.” Safi shivered. “He smelled my magic, just like the tales say, and now he can hunt me.”

“Which means he could be tracking us right now me.” Frost ran down Iseult’s back. Jolted in her shoulders. She scoured at her blade all the harder.

Normally, the act of cleaning helped her find stasis. Helped her thoughts slow and her practicality rise to the surface. She was the natural tactician, while Safi was the one with the first sparks of an idea.

Initiate, complete.

Except no solutions came to Iseult right now. She and Safi could lie low and avoid city guards for a few weeks, but they couldn’t hide from a Bloodwitch.

Especially if that Bloodwitch knew what Safi was—and could sell her to the highest bidder.

When a person stood directly before Safi, she could tell truth from lie, reality from deception. As far as Iseult had learned in her tutoring sessions with Mathew, the last recorded Truthwitch had died a century ago—beheaded by a Marstoki emperor for allying herself with a Cartorran queen.

If Safi’s magic ever became public knowledge, she would be used as a political tool …

Or eliminated as a political threat.

Safi’s power was that valuable and that rare. Which was why, for Safi’s entire life, she’d kept her magic secret. Like Iseult, she was a heretic: an unregistered witch. The back of Safi’s right hand was unadorned, and no Witchmark tattoo proclaimed her powers. Yet one of these days, someone other than Safi’s closest friends would figure out what she was, and when that day came, soldiers would storm the Silk Guildmaster’s guest room and drag away Safi in chains.

Soon, the girls’ blades were cleaned and resheathed, and Safi was pinning Iseult with one of her harder, more contemplative stares.

“Out with it,” Iseult ordered.

“We may have to flee the city, Iz. Leave the Dalmotti Empire entirely.”

Iseult rolled her salty lips together, trying not to frown. Trying not to feel.

The thought of abandoning Veñaza City … Iseult couldn’t do it. The capital of the Dalmotti Empire was her home. The people in the Northern Wharf District had stopped noticing Iseult’s pale Nomatsi skin or her angled Nomatsi eyes.

And it had taken her six and a half years to carve out that niche.

“For now,” Iseult said quietly, “let’s worry about getting into the city unseen—and let’s pray, too, that the Bloodwitch didn’t actually smell your blood.” Or your magic.

Safi huffed a weary sigh and nestled into a beam of sunlight. It made her skin glow, her hair luminescent. “To whom should I pray?”

Iseult scratched at her nose, grateful to have the subject shift. “We were almost killed by a Carawen monk, so why not pray to the Origin Wells?”

Safi gave a little shudder. “If that person prays to the Origin Wells, then I don’t want to. How about that Nubrevnan god? What’s His name?”

“Noden.”

“That’s the one.” Safi clasped her hands to her chest and stared up at the ceiling. “Noden, God of the Nubrevnan waves—”

“I think it’s all waves, Safi. And everything else too.”

Safi rolled her eyes. “God of all waves and everything else too, can you please make sure no one comes after us? Especially … him. Just keep him far away. And if you could keep the Veñaza City guards away too, that would be nice.”

“This is easily the worst prayer I have ever heard,” Iseult declared.

“Weasels piss on you, Iz. I’m not done yet.” Safi heaved a sigh through her nose and then resumed her prayer. “Please return all of Mathew’s money to me before he or Habim get back from their trip. And … that is all. Thank you very much, oh sacred Noden.” Then, she hastily added, “Oh, and please ensure that Chiseled Cheater gets exactly what he deserves.”

Iseult almost snorted at that last request—except a wave crashed into the lighthouse, rough and sudden against the stone. Water splattered Iseult’s face, and she swiped it away, agitated. Warm instead of cool.

“Please, Noden,” she whispered, rubbing sea spray off her forehead. “Please just get us through this alive.”

THREE

Reaching Mathew’s coffee shop where Iseult lived proved harder than Safi had anticipated. She and Iseult were exhausted, hungry, and bruised to hell-flames, so even the basic act of walking made Safi want to groan. Or sit down. Or at least ease her aches with a hot bath and pastries.

But baths and pastries weren’t happening any time soon. Guards swarmed everywhere in Veñaza City, and by the time the girls had straggled into the Northern Wharf District, it was almost dawn. They’d spent half the night hiking blearily from their lighthouse to the capital and then the other half of the night slinking through alleys and clambering over kitchen gardens.

Every flash of white—every dangling piece of laundry, every torn sailcloth or tattered curtain—had punched Safi’s stomach into her mouth. But it was never the Bloodwitch, thank the gods, and right as night began fading into dawn, the sign to Mathew’s coffee shop appeared. It poked out of a narrow road branching off the main wharf-side avenue.

Real Marstoki Coffee

Best in Veñaza City

It was not, in fact, real Marstoki coffee—Mathew wasn’t even from the Empire of Marstok. Instead, the coffee was filtered and bland, catering to, as Habim always called it, “dull western palates.”

Mathew’s coffee was also not the best in the city. Even Mathew would admit that the dingy hole-in-the-wall in the Southern Wharf District had much better coffee. But up here on the northern edges of the capital, people didn’t wander in for coffee. They came in for business.

The sort of business Wordwitches like Mathew excelled at—the trade of rumors and secrets, the planning of heists and cons. He ran coffee shops all across the Witchlands, and any news about anything always reached Mathew first.

It was his Wordwitchery that had made Mathew the best choice for Safi’s tutor, since it allowed him to speak all tongues of the Witchlands.

More importantly, though, Mathew’s Heart-Thread, Habim, had worked for Safi’s uncle her entire life—both as a man-at-arms and a constantly displeased instructor. So when Safi had been sent south, it had only made sense for Mathew to take over where Habim had left off.

Not that Habim had completely abandoned Safi’s training. He visited his Heart-Thread often in Veñaza City—and then proceeded to make Safi’s life miserable with extra hours of speed drills or ancient battle strategies.

Safi reached the coffee shop first and after hopping a puddle of sewage that was frighteningly orange, she began tapping out the lock-spell on the front door—a recent installment since the stolen cutlery incident. Habim could complain to Mathew all he wanted about the cost of an Aetherwitched lock-spell, but as far as Safi could see, it was worth the money. Veñaza City had a hefty crime rate—first because it was a port, and second because wealthy Guildmasters were just so appealing to piestra-hungry lowlifes.

Of course, it was those same elected Guildmasters that also paid for an extensive, seemingly endless collection of city guards—one of whom was pausing right at the alleyway’s mouth. He faced away, scanning the moored ships of the Northern Wharf District.

“Faster,” Iseult muttered behind her. She prodded Safi’s back. “The guard is turning … turning…”

The door flew wide, Iseult shoved, and Safi toppled into the dark shop.

“What the rut?” she hissed, rounding on Iseult. “The guards know us around here!”

“Exactly,” Iseult retorted, shutting the door and bolting the locks. “But from afar, we look like two peasants busting into a locked up coffee shop.”

Safi mumbled an unwilling, “Good point,” as Iseult stepped forward and whispered, “Alight.”

At once twenty-six bewitched wicks guttered to life, revealing bright, curly Marstoki designs on the walls, the ceiling, the floor. It was overdone—too many rugs of clashing patterns leapt at Safi—but like the coffee, westerners had a certain idea about how a Marstoki shop ought to look.

With the sigh of someone finally able to breathe, Iseult strode toward the spiral staircase in the back corner. Safi followed. Up, up they went, first to the second story, where Mathew and Habim lived. Next, to the slope-ceilinged attic that Iseult called home, its narrow space crowded with two cots and a wardrobe.

For six and a half years now, Iseult had lived and studied and worked here. After she’d fled her tribe, Mathew had been the only employer willing to not only hire and lodge a Nomatsi.

Iseult hadn’t moved away since—though not for a lack of wanting to.

A place of my own.

Safi must’ve heard her Threadsister say that a thousand times. A hundred thousand times. And maybe if Safi had grown up sharing a bed with her mother in a one-room hut as Iseult had, then she’d want a wider, more private, more personal space as well.

Yet … Safi had ruined all of Iseult’s plans. Every single saved piestra was gone, and all of the Veñaza City guards were actively hunting Safi and Iseult. It was literally the worst-case scenario possible, and no emergency satchel or hiding in a lighthouse was going to get them through this mess.

Gulping back nausea, Safi staggnered to a window across the narrow room and shoved it open. Hot, fish-saturated air wafted in, familiar and soothing. With the sun just rising in the east, the slate rooftops of Veñaza City shone like orange flames.

It was beautiful, tranquil, and gods below, Safi loved that view. Having grown up in drafty ruins in the middle of the Orhin Mountains—having been locked away in the eastern wing whenever Uncle Eron was in one of his moods, Safi’s life in the Hasstrel castle had been filled with broken windows and snow seeping in. With frozen winds and dank, slithering mold. Everywhere she looked, her eyes would land on carvings or paintings or tapestries of the Hasstrel mountain bat. A grotesque, dragon-like creature with the motto “Love and Dread” scrolling through its talons.

But the bridges and canals of Veñaza City were always sunbaked and smelling wonderfully of rotten fish. Mathew’s shop was always bright and crowded. The wharves always filled with sailors’ deliciously offensive oaths.

Here, Safi felt warm. Here, she felt welcome, and sometimes, she even felt wanted.

Safi cleared her throat. Her hand fell from the latch, and she turned to find Iseult changing into a gown of olive green.

Iseult dipped her head to the wardrobe. “You can wear my extra day gown.”

“That’ll show these, though.” Safi rolled up a salt-stiffened sleeve to reveal scrapes and bruises peppering her arms—all of which would be visible in the short, capped sleeves that were in style.

“Then it’s lucky for you I still have…” Iseult swept two cropped black jackets from the wardrove. “These!”

Safi’s lips crooked up. The jackets were standard attire for all Guild apprentices—and these two in particular were trophies from the girls’ first holdup.

“I still maintain,” Safi declared, “that we should’ve taken more than just their jackets when we left them tied up in the storeroom.”

“Yes, well, next time someone ruins a silk shipment and blames you, Saf, I promise we’ll take more than just their jackets.” Iseult tossed the black wool to Safi, who swooped it from the air.

As she hastily tore off her clothes, Iseult settled on the edge of her cot, lips pursed to one side. “I’ve been thinking,” she began evenly. “If that Bloodwitch is really after us, then maybe the Silk Guildmaster could protect you. He’s your technical guardian after all, and you do live in his guest room.”

“I don’t think he’ll harbor a fugitive.” Safi’s face tightened with a wince. “It wouldn’t be right to drag Guildmaster Alix into this anyway. He’s always been so kind to me, and I’d hate to repay him with trouble.”

“All right,” Iseult said, expression unchanging. “My next plan involves the Hell-Bards. They’re in Veñaza City for the Truce Summit, right? To protect the Cartorran Empire? Maybe you could appeal to them for help since your uncle used to be one—and I doubt even the Dalmotti guards would be stupid enough to cross the Emperor’s personal knights.”

Safi’s wince only deepened at that idea. “Uncle Eron was a dishonorably discharged Hell-Bard, Iz. The entire Hell-Bard Brigade now hates him, and Emperor Henrick hates him even more.” She snorted, a disdainful sound that skittered off the walls and rattled in her belly. “To make it worse, the Emperor is looking for any excuse to hand over my title to one of his slimy sycophants. I’m sure that holding up a Guildmaster is sufficient reason to do so.”

For most of Safi’s childhood, her uncle had trained her like a soldier and treated her like one too—whenever he’d been sober enough to pay attention, at least.

But when Safi had turned twelve, Emperor Henrick had decided it was time Safi come to the Cartorran capital for her education. What does she know of leading farmers or organizing a harvest? Henrick had bellowed at Uncle Eron, while Safi had waited, small and silent, behind him. What experience does Safiya have running a household or paying tithes?

It was that last concern—the paying of exorbitant Cartorran taxes—that had Emperor Henrick the most concerned. With all of the nobility wrapped around his ring-clad fingers, he wanted to ensure he had Safi ensnared too.

But Henrick’s attempt to nab one more loyal domna had fallen apart, for Uncle Eron hadn’t sent Safi to study in Praga with all the other young nobles. Instead, Eron had packed her off to the south, to the Guildmasters and tutors of Veñaza City.

It was the first and last time Safi had ever felt anything like gratitude for her uncle.

“In that case,” Iseult said, tone final and shoulders sagging, “I think we’ll have to leave the city. We can hole up … somewhere until all of this blows over.”

Safi bit her lip. Iseult made it sound so easy to “hole up somewhere,” but the reality was that Iseult’s clear Nomatsi ancestry made her a target wherever she went.

The one time the girls had tried leaving Veñaza City, to visit a friend nearby, they’d barely made it back home.

Of course, the three men at the tavern who’d decided to attack Iseult had never made it back home at all. At least not with intact femurs.

Safi stomped to the wardrobe and wrenched it open, pretending the handle was the Chiseled Cheater’s nose. If she ever—ever—saw that bastard again, she was going to break every bone in his blighted body.

“Our best bet,” Iseult went on, “will be the Southern Wharf District. The Dalmotti trade ships are berthed there, and we might be able to get passage in exchange for work. Do you need anything from Guildmaster Alix’s?”

At Safi’s headshake, Iseult continued, “Good. Then we’ll leave notes for Habim and Mathew explaining everything. Then … I guess we’ll … leave.”

Safi stayed silent as she towed out a golden gown. Her throat was too tight for words. Her stomach spinning too hard.

It was, as Safi fastened the ten million wooden buttons and Iseult tied a pale gray scarf around her head, that a knocking burst through the shop.

“Veñaza City Guard!” came a muffled voice. “Open up! We saw you break in!”

Iseult sighed—a sound of such long, long-suffering.

“I know,” Safi growled, sliding the last button in place. “You told me so.”

“Just so long as you’re aware.”

“Like you’ll ever let me forget?”

Iseult’s lips twitched with a smile, but it was a false attempt—and Safi didn’t need her Truthwitchery to see that.

As the girls tugged on their scratchy apprentice jackets, the guard started his bellowing again. “Open up! There’s only one way in or out of this shop!”

“Not true,” Safi inserted.

“We won’t hesitate to use force!”

“And nor will we.” At a nod from her Threadsister, Safi scooted to Iseult’s bed. Then they both dragged the cot toward the door. Wooden feet groaned, and soon enough they had it heaved on its side to form a barricade—one they knew worked well, for this was hardly the first time she and Iseult had been forced to sneak out.

Although it had always been Mathew and Habim bellowing on the other side. Not armed guards.

Moments later, Safi and Iseult stood at the window, breathing fast and listening as the front door smashed inward. As the entire shop quaked and glass shattered.

Cringing, Safi clambered onto the roof. First she’d lost Mathew’s money, and now she’d ruined his shop. Maybe … maybe it was a good thing her tutors were out of town on business. At least she wouldn’t have to face Mathew or Habim any time soon.

Iseult scrabbled out beside Safi, the emergency satchel on her back bulging with supplies. Iseult’s weapons fit into calf-scabbards beneath her skirt, but Safi could only stow her parrying knife in her boot. Her sword—her beautiful folded steel sword—was staying behind.

“Where to?” Safi asked, knowing her Threadsister had a route spinning behind her glittering eyes.

“We’ll head inland, as if we’re going to Guildmaster Alix’s, and then aim south.”

“Rooftops?”

“For as long as we can. You lead the way.”

Safi nodded curtly before kicking into a run—west, toward the inner heart of Veñaza City—and when she reached the edge of Mathew’s roof, she leaped for the next slope of shingles.

She slammed down. Pigeons burst upward, wings flapping to get out of the way, and then Iseult bounded down beside her.

But Safi was already moving, already flying for the next roof. And the next roof after that, on and on with Iseult right behind.

Iseult slunk along the cobblestoned street, Safi two steps ahead. The girls had veered inland from the coffee shop, crossing canals and looping back over bridges to avoid city guards. Fortunately, morning traffic had begun—a teeming mass of fruit-laden carts, donkeys, goats, and people of all race and nationality. Threads with colors as varied as their owner’s skins swirled lazily through the heat.

Safi skipped in front of a swine cart, leaving Iseult to chase after her. Then it was around a beggar, past a group of Purists shouting about the sins of magic, and then directly through a herd of unhappy sheep before the girls reached a clogged mass of unmoving traffic. Ahead, Threads swirled with red annoyance at the holdup.

Iseult imagined her own Threads were just as red. The girls were so close to the Southern Wharf District that Iseult could even see the hundreds of white-sailed ships berthed ahead.

But she embraced the frustration. Other emotions—ones she didn’t want to name and that no decent Threadwitch would ever allow to the surface—shivered in her chest. Stasis, she told herself, just as her mother had taught years ago. Stasis in your fingertips and your toes.

Soon, the Threads of traffic flickered with cyan understanding. The color moved like a snake across a pond, as if the crowds were learning, one by one, the reason for this traffic jam.

Back, back the color moved until at last an old biddy near the girls squawked, “What? A blockade up ahead? But I’ll miss the freshest crabs!”

Iseult’s gut turned icy—and Safi’s Threads flashed with gray fear.

“Hell-gates,” she hissed. “Now what, Iz?”

“More brazening, I think.” With a grunt and shifting of her weight, Iseult fished out a thick gray tome from her pack. “We’ll look like two very studious apprentices if we’re carrying books. You can take A Brief History of Dalmotti Autonomy.”

“Brief my behind,” Safi muttered, though she did accept the enormous book. Next, Iseult hauled out a blue hide-bound volume titled An Illustrated Guide to the Carawen Monastery.

“Oh, now I see why you really have these.” Safi lifted her eyebrows, daring Iseult to argue. “They aren’t for disguise at all. You just didn’t want to leave behind your favorite book.”

“And?” Iseult sniffed dismissively. “Does this mean you don’t want to carry it?”

“No, no. I’ll keep it.” Safi popped her chin high. “Just promise that you’ll let me do all the acting once we reach the guards.”

“Act away, Saf.” Grinning to herself, Iseult tugged her scarf low. It was soaked through with sweat, but it still shaded her face. Her skin. Then she adjusted her gloves until not an inch of wrist was visible. All the focus would be on Safi and would stay on Safi.

For as Mathew always said, With your right hand, give a person what he expects—and with your left hand, cut his purse. Safi always played the distracting right hand—and she was good at it—while Iseult lurked in the shadows, ready to claim whatever purse needed cutting.

As Iseult settled into a boiling wait, she creaked back her book’s thick cover. Ever since a monk had helped Iseult when she was a little girl, Iseult had been somewhat … well, obsessed was the word Safi always used. But it wasn’t just gratitude that had left Iseult fascinated by the Carawens—it was their pure robes and gleaming opal earrings. Their deadly training and sacred vows.

Life at the Carawen monastery seemed so simple. So contained. No matter one’s heritage, one could join and have instant acceptance. Instant respect.

It was a feeling Iseult could scarcely imagine yet her heart beat hungrily every time she thought of it.

The book’s pages rustled open to page thirty-seven—to where a bronze piestra shone up at her. She had wedged the coin there to mark her last page, and its winged lion seemed almost to laugh at her.

The first piestra toward our new life, Iseult thought. Then her eyes flickered over the ornate Dalmotti script on the page. Descriptions and images of different Carawen monks scrolled across it, the first of which was Mercenary Monk, its illustration all knives and sword and stony expression.

It looked just like the Bloodwitch from yesterday.

Blood. Witch. Blood. Witch.

Ice pooled in Iseult’s belly at the memory of his red eyes. His bared teeth. Ice … and something hollower. Heavier.

Disappointment, she finally pinpointed, for it seemed so vastly wrong that a monster such as he should be allowed into the monastery’s ranks.

Iseult glanced at the caption beneath the illustration, as if this might offer some explanation. Yet all she read was, Trained to fight abroad in the name of the Cahr Awen.

Iseult’s breath slid out at that word—Cahr Awen—and her chest stretched tight. As a girl, she’d spent hours, climbing trees and pretending she was one of the Cahr Awen—that she was one of the two witches born from the Origin Wells who could cleanse even the darkest evils.

But just as many of the springs feeding the Wells had been dead for centuries, no new Cahr Awen had been born in almost five hundred years—and Iseult’s fantasies had inevitably ended with gangs of village children. They would swarm whatever tree she’d clambered into, shouting up curses and hate that they’d learned from their parents. A Threadwitch who can’t make Threadstones doesn’t belong here!

Iseult had always known in those moments—as she hugged a tree branch tight and prayed that her mother would find her soon—that the Cahr Awen was nothing more than a pretty story.

Gulping, Iseult heaved aside those memories. This day was bad enough; no need to dredge up old miseries too. Besides, she and Safi were almost to the guards now, and Habim’s oldest lesson was whispering in the back of her mind.

Evaluate your opponents, he always said. Analyze your terrain. Choose your battlefields when you can.

“Single-file lines!” the guards called. “Any weapons must be out where we can see them!”

Iseult clapped her book shut in a whoof! of musty air. Ten guards, she counted. Spread out across the road with carts stacked behind them to block the crowd. Crossbows. Cutlasses. If this little interrogation didn’t go well, then there was no way the girls could fight their way through.

“All right,” Safi muttered. “It’s our turn. Keep your face hidden.”

Iseult did as ordered and sank into position behind Safi—who marched imperiously up to the first sour-faced guard.

“What is the meaning of this?” Safi’s words rang out, clear and clipped over the constant din of traffic. “We are now late to our meeting with the Wheat Guildmaster. Do you know what his temper is like?”

The guard’s face settled into a bored glower—but his Threads flashed with keen interest. “Names.”

“Safiya. And this is my lady-in-waiting, Iseult.”

Though the guard’s expression remained unimpressed, his Threads flared with more interest. He angled away, motioning for a second guard to loom in close, and Iseult had to bite her tongue not to warn Safi.

“I demand to know what this holdup is for!” Safi cried at the new guard, a giant of a man.

“We’re lookin’ for two girls,” he rumbled. “They’re wanted for highway robbery. I don’t suppose you have any weapons on you?”

“Do I look like the sort of girl to carry a weapon?”

“Then you won’t mind if we search you.”

To Safi’s credit, none of the fear in her Threads showed on her face, and she only lifted her chin higher. “I most certainly do mind, and if you so much as touch my person, then I will have you fired immediately. All of you!” She thrust out her book, and the first guard flinched. “At this time tomorrow, you’ll be on the streets and wishing you hadn’t messed with a Guildmaster’s apprentice—”

Safi didn’t get to finish her threat, for at that moment, a gull screamed overhead … and a splattering of white goo landed on her shoulder.

Her Threads flashed to turquoise surprise. “No,” she breathed, eyes bulging. “No.”

The guards’ eyes bulged too, their Threads now shimmering into a giddy pink.

They erupted with laughter. Then they started pointing, and even Iseult had to clap a gloved hand to her mouth. Don’t laugh, don’t laugh—

She started laughing, and Safi’s Threads blazed into red fury. “Why?” she squawked at Iseult. Then at the guards. “Why always me? There are a thousand shoulders for a gull to crap on, but they always pick me!”

The guards were doubled over now, and the second one lifted a limp hand. “Go. Just … go.” Tears streamed from his eyes—which only served to make Safi snarl as she stomped past, “Why don’t you do something useful with your time? Instead of laughing at girls in distress, go fight crime or something!”

Then Safi was through the checkpoint and racing for the nearest fat-hulled trade ships—with Iseult right on her heels and laughing the entire way.

FOUR

Merik Nihar’s fingers curled around the butter knife. The Cartorran domna across the wide oak dining table had a hairy chin with chicken grease oozing down it.

As if sensing Merik’s gaze, the domna lifted a beige napkin and dabbed at her wrinkled lips and puckered chin.

Merik hated her—just as he hated every other diplomat here. He might’ve spent years mastering his family’s famous temper, yet all it would take at this point was one more grain. One more grain of salt, and the ocean would flood.

Throughout the long dining room, voices hummed in at least ten different languages. The Continental Truce Summit would begin tomorrow to discuss the Great War and the close of the Twenty Year Truce. It had brought hundreds of diplomats from across the Witchlands to Veñaza City.

Dalmotti might have been the smallest of the three empires, but it was the most powerful in trade. And since it was neatly situated between the Empire of Marstok in the east and the Cartorran Empire to the west, it was the perfect place for these international negotiations.

Merik was here to represent Nubrevna, his homeland. He’d actually arrived three weeks earlier, hoping to open new trade—or perhaps reestablish old Guild connections. But it had been a complete waste of time.

Merik’s eyes flicked from the old noblewoman to the enormous expanse of glass behind her. The gardens of the Doge’s palace shone beyond, suffusing the room in a greenish glow and the scent of hanging jasmine. As elected leader of the Dalmotti Council, the Doge had no family—no Guildmasters in Dalmotti did since families were said to distract them from their devotion to the Guilds—so it wasn’t as if he needed a garden that could hold twelve of Merik’s ships.

“You are admiring the glass wall?” asked the ginger-haired leader of the Silk Guild, seated on Merik’s right. “It is quite a feat of our Earthwitches. It’s all one pane, you know.”

“Quite a feat, indeed,” Merik said, though his tone suggested otherwise. “Although I wonder, Guildmaster Alix, if you’ve ever considered a more useful occupation for your Earthwitches.”

The Guildmaster coughed lightly. “Our witches are highly specialized individuals. Why insist that an Earthwitch who is good with soil only work on a farm?”

“But there is a difference between a Soilwitch who can only work with soil and an Earthwitch who chooses to only work with soil. Or with melting sand into glass.” Merik leaned back in his chair. “Take yourself, Guildmaster Alix. You are an Earthwitch, I presume? Likely your magic extends to animals, yet certainly it’s not exclusive to only silkworms.”

“Ah, but I am not an Earthwitch at all.” Alix flipped his hand slightly, revealing his Witchmark: a circle for Aether and a dashed line that meant he specialized in art. “I am a tailor by trade. My magic lies in bringing a person’s spirit to life in clothing.”

“Of course,” Merik answered flatly. The Silk Guildmaster had just proven Merik’s point—not that the man seemed to notice. Why waste a magical skill with art on fashion? On a single type of fabric? Merik’s own tailor had done a plenty fine job with the linen suit he now wore—no magic necessary.

A long, silver gray frock coat covered a cream shirt, and though both pieces had more buttons than ought to be legal, Merik liked the suit. His fitted black breeches were tucked into squeaking, new boots, and the wide belt at his hips was more than mere decoration. Once Merik was back on his ship, he would refasten his cutlass and pistols.

Clearly sensing Merik’s displeasure, Guildmaster Alix shifted his attention to the noblewoman on his other side. “What say you to Emperor Henrick’s pending marriage, my lady?”

Merik’s frown deepened. All anyone seemed interested in discussing at this luncheon was gossip and frivolities. There was a man in the former Republic of Arithuania—that wild, anarchical land to the north—who was uniting raider factions and calling himself “king,” but did these imperial diplomats care?

Not at all.

There were rumors that the Hell-Bard Brigade was pressing witches into service, yet not a one of these doms or domnas seemed to find this news alarming. Then again, Merik supposed it wasn’t their sons or daughters who would be forced to enlist.

Merik’s furious gaze dropped back to his plate. It was scraped clean. Even the bones had been swept into his napkin. Bone broth, after all, was easy to make and could feed sailors for days. Several of the other luncheon guests had noticed—Merik hadn’t exactly hidden it when he used the beige silk to pluck the bones from his plate.

Merik was even tempted to ask his nearest neighbors if he could have their chicken bones, most of which were untouched and surrounded by green beans. Sailors didn’t waste food—not when they never knew if they would catch another fish or see land again.

And especially not when their homeland was starving.

“Admiral,” said a fat nobleman to Merik’s left. “How is King Serafin’s health? I heard his wasting disease was in its final stages.”

“Then you heard wrong,” Merik answered, his voice dangerously cool for anyone who knew the Nihar family rage. “My father is improving. Thank you … what’s your name again?”

The man’s cheeks jiggled. “Dom Phillip fon Grieg.” He pasted on a fake smile. “Grieg is one of the largest holdings in the Cartorran Empire—surely you know of it. Or … do you? I suppose a Nubrevnan would have no need for Cartorran geography.”

Merik merely smiled at that. Of course he knew where the Grieg holdings were, but let the dom think him ignorant to Cartorran specifics.

“I have three sons in the Hell-Bard Brigade,” the dom continued, his thick, sausage-like fingers reaching for his goblet of wine. “The Emperor has promised them each a holding of their own in the near future.”

“You don’t say.” Merik was careful to keep his face impassive, but in his head, he was roaring his fury. The Hell-Bard Brigade—that elite contingent of ruthless fighters tasked with “cleansing” Cartorra of elemental witches and heretics—they were one of the primary reasons that Merik hated Cartorrans.

After all, Merik was an elemental witch, as was almost every person in the Witchlands that he cared about.

As Dom fon Grieg sipped from his goblet, a stream of expensive Dalmotti wine dribbled out the sides of his mouth. It was wasteful. Disgusting. Merik’s fury grew … and grew … and grew.

Until it was the final grain of salt, and Merik succumbed to the flood.

With a sharp, rasping inhale, he drew the air in the room to himself. Then he huffed it out.

Wind blasted at the dom. The man’s goblet tipped up; wine splattered his face, his hair, his clothes. It even flew to the window—splattering red droplets across the glass.

Silence descended. For half a second, Merik considered what he ought to do now. An apology was clearly out of the question, and a threat seemed too dramatic. Then Merik’s eyes caught on Guildmaster Alix’s uncleared plate. Without a second thought, Merik shoved to his feet and swept a stormy glare over the noble faces now gawking at him. At the wide-eyed servants hovering in the doorways and shadows.

Then, Merik snatched the napkin from the Guildmaster’s lap. “You’re not going to eat that, are you?” Merik didn’t wait for an answer. He merely murmured, “Good, good—because my crew most certainly will,” and set to gathering up the bones, the green beans, and even the final bits of stewed cabbage. After wrapping the silk napkin tight, he thrust it into his waistcoat pocket along with his own saved bones.

Then he turned to the blinking Dalmotti Doge, and declared, “Thank you for your hospitality, my lord.”

And with nothing more than a mocking salute, Merik Nihar, prince of Nubrevna and admiral to the Nubrevnan navy, marched from the Doge’s luncheon, the Doge’s dining room, and finally the Doge’s palace.

And as he walked, he began to plan.

By the time Merik reached the southernmost point of the Southern Wharf District, distant chimes were ringing in the fifteenth hour and the tide was out. The heat of the day had sunk into the cobblestones, leaving a miserable warmth to curl up from the streets.

When Merik attempted to hop a puddle of only Noden knew what, he failed and his new boots caught the edge of it. Blackened water splashed up, carrying with it the heavy stench of old fish—and Merik fought the urge to punch in the nearest shop window. It wasn’t the city’s fault that its Guildmasters were buffoons.

In the nineteen years and four months since the Twenty Year Truce had stopped all war in the Witchlands, the three empires—Cartorra, Marstok, and Dalmotti—had successfully crushed Merik’s home through diplomacy. Each year, one less trade caravan had passed through his country and one less Nubrevnan export had found a buyer.

Nubrevna wasn’t the only small nation to have suffered. Supposedly, the Great War had started, all those centuries ago, as a dispute over who owned the Five Origin Wells. In those days, it was the Wells that chose the rulers—something to do with the Twelve Paladins … Although how twelve knights or an inanimate spring could choose a king, Merik had never quite understood.

It was all the stuff of legends now anyway, and over the decades and eventually the centuries, three empires grew from the Great War’s mayhem—and each empire wanted the same thing: more. More witcheries, more crops, more ports.

So then it was three massive empires against a handful of tiny, fierce nations—tiny fierce nations who slowly got the upper hand, for wars cost money, and even empires can run out.

Peace, the Cartorran emperor had proclaimed. Peace for twenty years, and then a renegotiation. It had sounded perfect.

Too perfect.

What people like Merik’s mother hadn’t realized when they’d penned their names on the Twenty Year Truce was that when Emperor Henrick said Peace!, he really meant Pause. And when he said Renegotiation, he meant Ensuring these other nations fall beneath us when our armies resume their march.

So now, as Merik watched the Dalmotti armies roll in from the west, the Marstoki Firewitches gather in the east, and three imperial navies slowly float toward his homeland’s coast, it felt like Merik—and all of Nubrevna—were drowning. They were sinking beneath the waves, watching the sunlight vanish, until there would be nothing left but Noden’s Hagfishes and a final lungful of water.

But the Nubrevnans weren’t crippled yet.

Merik had one more meeting—this one with the Gold Guild. If Merik could just open one line of trade, then he felt certain other Guilds would follow.

When at last Merik reached his warship, a three-masted frigate with the sharp, beak-like bow distinctive to Nubrevnan naval ships, he found her calm upon the low tide. Her sails were furled, her oars stowed, and the Nubrevnan flag, with its black background and bearded iris—a vivid flash of blue at the flag’s center—flew languidly on the afternoon breeze.

As Merik marched up the gangway onto the Jana, his temper settled slightly—only to be replaced by shoulder-tensing anxiety and the sudden need to check if his shirt was properly tucked in.

This was Merik’s father’s ship; half the men were King Serafin’s crew; and despite three months with Merik in charge, these men weren’t keen on having Merik around.

A towering, ash-haired figure loped over the main deck toward Merik. He dodged several swabbing sailors, stretched his long legs over a crate, and then swept a stiff bow before his prince. It was Merik’s Threadbrother, Kullen Ikray—who was also first mate on the Jana.

“You’re back early,” Kullen said. When he rose, Merik didn’t miss the red spots on Kullen’s pale cheeks, or the slight hitch in his breath. It meant the possibility of a breathing attack.

“Are you ill?” Merik asked, careful to keep his voice low.

Kullen pretended not to hear—though the air around them chilled. A sure sign Kullen wanted to drop the subject.

At first glance, nothing about Merik’s Threadbrother seemed particularly fit for life at sea: he was too tall to fit comfortably belowdecks, his fair skin burned with shameful ease, and he wasn’t fond of swordplay. Not to mention, his thick white eyebrows showed far too much expression for any respectable seaman.

But by Noden, if Kullen couldn’t control a wind.

Unlike Merik, Kullen’s elemental magic wasn’t exclusive to air currents—he was a full Airwitch, able to control a man’s lungs, able to dominate the heat and the storms, and once, he’d even stopped a full-blown hurricane. Witches like Merik were common enough and with varying degrees of mastery over of the wind, but as far as Merik knew, Kullen was the only living person with complete control over all aspects of the air.

Yet it wasn’t even Kullen’s magic that Merik most valued. It was his mind, sharp as nails, and his steadiness, constant as the tide to the sea.

“How was the lunch?” Kullen asked, the air around him warming as he bared his usual terrifying smile. He wasn’t very good at smiling.

“It was a waste of time,” Merik replied. He marched over the deck, his boot heels clacking on the oak. Sailors paused to salute, their fists pounding their hearts. Merik nodded absently at each.

Then he remembered something in his pocket. He withdrew the napkins and handed them off to Kullen.

Several breaths passed. Then, “Leftovers?”

“I was making a point,” Merik muttered, and his footsteps clipped out harder. “A stupid point that missed its mark. Is there any word from Lovats?”

“Yes—but,” Kullen hastened to add, hands lifting, “it had nothing to do with the King’s health. All I heard was that he’s still confined to bed.”

Frustration towed at Merik’s shoulders. He hadn’t heard any specifics about his father’s disease in weeks. “And my aunt? Is she back from the healer’s?”

“Hye.”

“Good.” Merik nodded—at least satisfied with that. “Send Aunt Evrane to my cabin. I want to ask her about the Gold Guild…” Merik trailed off, feet grinding to a halt. “What is it? You only squint at me like that when something’s wrong.”

“Hye,” Kullen acknowledged, scratching at the back of his neck. His eyes flicked toward the massive wind-drum on the quarterdeck. A new recruit—whose name Merik could never remember—was cleaning the drum’s two mallets. The magicked mallet, for producing cannon-like bursts of wind. The standard mallet, for messages and shanty-beats.

“We should discuss it in private,” Kullen finally finished. “It’s about your sister. Something … arrived for her.”

Merik smothered an oath, and his shoulders rose higher. Ever since Serafin had named Merik as the Truce Summit’s Nubrevnan envoy—meaning he was also temporarily Admiral of the Royal Navy—Vivia had tried a thousand different ways to seize control from afar.

Merik stomped into his cabin, footsteps echoing off the whitewashed ceiling beams as he aimed for the screwed-down bed in the right corner.

Kullen, meanwhile, moved to the long table for charts and bookkeeping at the center of the room. It was also bolted down, and a three-inch rim kept papers from flying during rough seas.

Sunlight cut through windows all around, reflecting on King Serafin’s sword collection, meticulously displayed on the back wall—the perfect place for Merik to accidentally touch one in his sleep and leave permanent fingerprints.

At the moment, this ship might have been Merik’s, but Merik had no illusions that it would stay that way. During times of war, the Queen ruled the land and the King ruled the seas. Thus, the Jana was Merik’s father’s ship, named after the dead Queen, and it would be Serafin’s ship once more when he healed.

If he healed—and he had to. Otherwise, Vivia was next in line for the throne … and that wasn’t something Merik wanted to imagine yet. Or deal with. Vivia was not the sort of person content with only ruling land or sea. She wanted control of both—and beyond—and she made no effort to pretend otherwise.

Merik knelt beside his only personal item on the ship: a trunk, roped tightly to the wall. After a quick rummage, he found a clean shirt and his storm-blue admiral’s uniform. He wanted to get out of his dress suit as quickly as possible, for there was nothing to deflate a man’s ego like a bit of frill around the collar.

As Merik’s fingers undid the ten million buttons on his dress shirt, he joined Kullen at the table.

Kullen had opened a map of the Jadansi Sea—the slip of ocean that bisected the Dalmotti Empire. “This is what came for Vivia.” He plunked down a miniature ship that looked identical to the Dalmotti Guild ships listing outside. It slid across the map, locking in place over Veñaza City. “Obviously, it’s Aetherwitched and will move wherever its corresponding ship sails.” Kullen’s eyes flicked up to Merik’s. “According to the scumbag who delivered it, the corresponding ship is from the Wheat Guild.”

“And why,” Merik began, giving up on his buttons and just yanking the shirt over his head, “does Vivia care about a trade ship?” He tossed it at his trunk and planted his hands on the table. His faded Witchmark stretched into an unbalanced diamond. “What does she expect us to do with it?”

“Foxes,” Kullen said, and the room turned icy.

“Foxes,” Merik repeated, the word knocking around without meaning in his skull. Then suddenly, it sifted into place—and he burst into action, spinning for his trunk. “That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard from her—and she’s said plenty of stupid things in her life. Tell Hermin to contact Vivia’s Voicewitch. Now. I want to talk with her at the next ring of the chime.”

“Hye.” Kullen’s bootsteps rang out as Merik yanked out the first shirt his fingers touched. He tugged it on as the cabin door swung wide … and then clicked shut.

At that sound, Merik gritted his teeth and fought to keep his temper quelled down. Locked up tight.

This was so typically Vivia, so why the Hell should Merik be surprised or angry?

Once upon a time, the Foxes had been Nubrevnan pirates. Their tactics had relied on small half-galleys, like Merik’s first ship. They were shallower than the Jana, with two masts and oars, allowing them to slip between sand bars and barrier islands with ease—and allowing them to ambush larger ships.

But the Fox standard—a serpentine sea fox coiling around the bearded iris—hadn’t flown the masts in centuries. It hadn’t needed to once Nubrevna had possessed a true navy of its own.

As Merik stood there trying to imagine any sort of argument his sister might listen to, something flickered outside the nearest window. Yet other than waves piling against the high-water mark and a merchant ship rocking next door, there was nothing unusual.

Except … it wasn’t high tide.

Merik darted for the window. This was Veñaza City—a city of marshes—and there were only two things that would bring in an unnatural tide: an earthquake.

Or magic.

And there was only one reason a witch would summon waves to a wharf.

Cleaving.

Merik sprinted for the door. “Kullen!” he roared as his feet hit the main deck. The waves were already licking higher, and the Jana had begun to list.

Two ships north, a hulking sailor staggered down a trade ship’s gangplank toward the cobblestoned street. He scratched furiously at his forearms, at his neck—and even at this distance, Merik could see the black pustules bubbling on the man’s skin. Soon his magic would reach its breaking point, and he would feast on the nearest human life.

The waves swept in higher, rougher—summoned by the cleaving witch. Though several people noticed the man and screeched their terror, most couldn’t see the waves, couldn’t hear the screams. They were unaware and unprotected.

So Merik did the only thing he could think of. He roared for Kullen, and then he gathered in his magic, so it would lift him high and carry him far.

Moments later, in a gust of air, Merik took flight.

FIVE

Safi’s temper was on the verge of exploding, what with the gull crap on her shoulder, the oppressive afternoon heat, and the fact that not one of the six ships on this dock needed new workers (especially not ones dressed as Guild apprentices).

Iseult glided more serenely ahead, already at the end of the dock and joining the wharfside throngs. Even from this distance, Safi could see Iseult fidgeted with her scarf and gloves as she scrutinized something in the murky water.

Eyebrows high, Safi directed her own gaze to the brackish waves. There was a charge in the air. It pricked at the hair on her arms and sent a chill fingering down her spine …

Then her Truthwitchery exploded—a coating, scraping sensation against her neck that heralded wrongness. Huge, vast wrongness.

Someone’s magic was cleaving.

Safi had felt it once before—felt her power swell as if it might cleave too. Anyone with a witchery could sense it coming. Could feel the world falling out of its magical order. Of course, if you didn’t have magic, like most of these people streaming down the dock, then you might as well be dead.

A shout split Safi’s ears like thunder. Iseult. Midstride and with a roar for people to “Stand aside!,” Safi dove forward, curled her chin to her chest and rolled. As her body tumbled over the wood, she grabbed for the parrying dagger in her boot. It was for defense against a sword, but it was still sharp.

And it could gut a man if needed.

As the momentum of the roll drove Safi back to her feet, she dragged the knife down, and in a quick slash, she shredded her skirts. Then she was sprinting once more, her legs free to pump as high as she needed—and her knife in hand.

The waves curled higher. Harder. Gusts of power that grated against Safi’s skin like a thousand lies told at once.

The cleaved man’s magic must be connected to water, and now the trade ships were heaving, heaving … creaking, creaking … and then crashing against the pier.

Safi reached the stone quay. In half a breath, she took in the scene: a cleaved Tidewitch, his skin rippling with the oil of festered magic and blood black as pitch dribbling from a cut on his chest.

Only paces away, Iseult was low in her stance—her skirts ripped through as well. That’s my girl, Safi thought.

And to the left, flying through the air with all the grace of an untested, broken-winged bat, was some sort of Airwitch. His hands were out as he called the wind to carry him.

Safi had only two thoughts: Who the rut is that Nubrevnan Windwitch? And: He should really learn how to button a shirt.

Then the shirtless man touched down directly in her path.

She shrieked as loud as she could, but all she got was an alarmed glance before she flung her knife aside and slammed into his body. They crashed to the ground—and the young man shoved her off, shouting, “Stay back! I’ll handle this!”

Safi ignored him—he was clearly an idiot—and in more time than it ought to take, she disentangled herself from the Nubrevnan and snatched up her dagger.

She spun toward the cleaving Tidewitch—just as Iseult closed in, a swirl of steel meant to attract the eye. But it was having no effect. The Tidewitch didn’t lurch out of the way. Iseult’s scythes beat into his stomach, and more black blood sprayed.

Blackened organs toppled out too.

Then water erupted onto the street. Ships rammed against the stones in a deafening crunch of wood. A second wave charged in, and right behind it, a third.

“Kullen!” the Nubrevnan bellowed from behind Safi. “Hold back the water!”

In an explosion of magic rushed across Safi’s body, air funneled toward the encroaching waves.

The magicked wind hit the water; waves toppled and foamed backward.

But the cleaving Tidewitch didn’t care. His blackened eyes had latched on to Safi now. His bloodstained hands clawed up and he barreled toward her like a squall.

Safi sprang into a flying kick. Her heel crashed into his knee; he toppled forward right as Iseult spun into a hook-kick. Her boot pummeled the man’s chin, shifted the angle of his fall.

He hit the cobblestones. Black pustules burst all over his skin, splattering the street with his blood.

But he was still alive—still conscious. With a roar like a hurricane, he struggled to get upright.

That was when the Nubrevnan man decided to reappear. He sidled close to the Cleaved—and Safi’s panic burned up her throat. “What are you doing?”

“I told you I’d handle this!” he bellowed. Then his arms flung back, and in a surge of power that sparked through Safi’s lungs, his cupped hands hit the cleaved sailor’s ears. Air exploded through the man’s brain. His blackened eyes rolled backward.

The Tidewitch crumpled to the street. Dead.

Iseult swept aside her skirts and shoved her moon scythes back into their concealed calf-scabbards. Nearby, Dalmottis made frantic two-fingered swipes across their eyes. It was a sign to ward off evil—to ask their gods to protect their souls. Some aimed their movements at the dead Cleaved, but more than a few aimed the swipe at Iseult.

As if she had any interest in claiming their souls.

She did, however, have an interest in not being mobbed and beaten today, so, twisting toward the dead Tidewitch, she readjusted her headscarf—and thanked the Moon Mother it hadn’t been removed in the fight.

She also thanked the goddess that no one else had cleaved. Such a powerful burst in magic could easily send other witches over the brink—a brink from which there was no coming back.

Though no one knew what made a person cleave, Iseult had read theories that linked the corruption to the five Origin Wells spread across the Witchlands. Each Well was linked to one of the five elements: Aether, Earth, Water, Wind, or Fire. Though people spoke of a Void element—and of Voidwitches like that Bloodwitch—there was no record of an actual Void Well.

Perhaps a Void Well was out there, but it had been long forgotten. The springs that had fed it were dried up. The trees that had blossomed year-round were shriveled to desiccated husks. Such stagnation had certainly happened with the Earth, Wind, and Water Wells, and perhaps they too would one day be lost to history.

No matter the Wells’ fates, though, scholars didn’t think it mere coincidence that the witcheries to cleave were those linked to Earth, Wind, or Water. And if the Carawen monks were to be believed, then only the return of the Cahr Awen could ever heal the dead Wells or the Cleaved.

Well, Iseult didn’t think that would be happening any time soon. No return of the Cahr Awen—and no escaping all these hateful stares, either.

Once Iseult felt certain that her hair was sufficiently covered, her face sufficiently shaded, and her sleeves sufficiently low enough to hide her pale skin, she reached for Safi’s Threads so she could find her Threadsister among the crowds.

But her eyes and her magic caught something off. Threads like she’d never seen before. Directly beside her … on the corpse.

Her gaze slid to the cleaved man’s body. Blackened blood … and perhaps something else oozed from his ears, between the cobblestones. The pustules on his body had erupted—some of that oily spray was on Iseult’s slashed skirts and sweaty bodice.

And yet, though the man was undoubtedly dead, there were still three Threads wriggling over his chest. Like maggots, they shimmied and coiled inward. Short Threads. The Threads that break.

It shouldn’t have been possible—Iseult’s mother had always told her that the dead have no Threads, and in all the Nomatsi burning ceremonies Iseult had attended to as a child, she had never seen Threads on a corpse.

The longer Iseult gaped, the more the crowds closed in. Spectators curious over the body were everywhere, and Iseult had to squint to see through their Threads. To tamp down on all the emotions around her.

Then one crimson, raging Thread flashed nearby—and with it came a waspish snarl. “Who the hell-flames do you think you are? We had that under control.”

“Under control?” retorted a male voice with a sharp accent. “I just saved your lives!”

“Are you Cleaved?” Safi cried—and Iseult winced at the poor word choice. But of course, Safi was venting her grief. Her terror. Her explosive Threads. She was always like this when something bad—truly bad—happened. She either ran from her emotions as fast as her legs would carry her or she beat them into submission.

When at last Iseult popped out beside her Threadsister, it was just in time to see Safi grab a fistful of the young man’s unbuttoned shirt.

“Is this how all Nubrevnans dress?” Safi snatched the other side of his shirt. “These go inside these.”

To his credit, the Nubrevnan didn’t move. His face simply flushed a wild scarlet—as did his Threads—and his lips pressed tight.

“I know,” he gritted out, “how a button operates.” He knocked Safi’s wrists away. “And I don’t need advice from a woman with bird shit on her shoulder.”

Oh no, Iseult thought, lips parting to warn—

Fingers clamped on Iseult’s arm. Before she could flip up her hand and snap the wrist of her grabber, the person flipped up her wrist and shoved it against her back.

And a Thread of clayish red pulsed in Iseult’s vision. It was a familiar shade of annoyance that spoke of years enduring Safi’s tantrums—which meant Habim had arrived.

The Marstoki man shoved Iseult’s wrist harder to her back and snarled, “Walk, Iseult. To that cats’ alley over there.”

“You can let me go,” she said, voice toneless. She could just see Habim from the corner of her eyes. He wore the Hasstrel family’s gray and blue livery.

“Voidwitch?! You called me a Voidwitch?! I speak Nubrevnan, you horse’s ass!” The rest of Safi’s bloodthirsty screams were in Nubrevnan—and swallowed up by the crowds.